Forests in South Asia carry a sound unlike any other continent. When dusk settles along riverbanks, and when monsoon winds sway thick sal trees and undergrowth, a deep resonant call sometimes echoes through the forest a call so powerful that even leopards pause. This is the voice of the sambar deer, Rusa unicolor, the largest wild deer species across India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. Its immense size, muscular frame, heavy build and dark-brown coat give it a presence close to wild cattle, yet its behaviour remains profoundly deer-like, cautious, elusive and shaped by millennia of jungle survival.

Milk is not something people associate with the sambar deer. The world speaks of sambar as a forest sentinel, a tiger’s primary prey, a night-moving herbivore, and an ecological engineer that shapes vegetation patterns. But the milk a sambar doe produces for her fawn is one of the densest, rarest, most nutritionally intense wild mammal milks in Asia. It is almost completely unstudied by global dairy literature. The milk exists entirely for the fawn alone, delivered in short intervals, hidden deep inside forests where predators constantly patrol. Understanding this milk opens a new door into how evolution builds nourishment not for agriculture but for jungle survival.

This article does not treat sambar deer milk as a product because it is not one. It treats it as a biological masterpiece.

- The Sambar Body: A Forest-Adaptive Giant

Unlike European deer designed for open landscapes, sambar deer thrive in dense vegetation, tall grasses, bamboo clusters, mixed deciduous forests and rainforest edges. Their physical build reflects this ecology. The doe stands tall and heavily structured, capable of powering through thick undergrowth. Her skin is tough, her muscles strong, her digestive system incredibly versatile, capable of processing grasses, leaves, shrubs, aquatic plants and seasonal forest fruits.

This ecological diversity shapes her milk. A sambar fawn is born into a forest where every sound may reveal danger. The mother hides the newborn in dense undergrowth, returns periodically for nursing, and guides mobility within days. This demands milk that builds strength rapidly — a dense, protein-rich, fat-heavy fluid designed to convert vulnerability into agility.

The milk becomes a biochemical extension of the mother’s powerful body.

- The Composition: Dense Fat, High Protein, Survival Chemistry

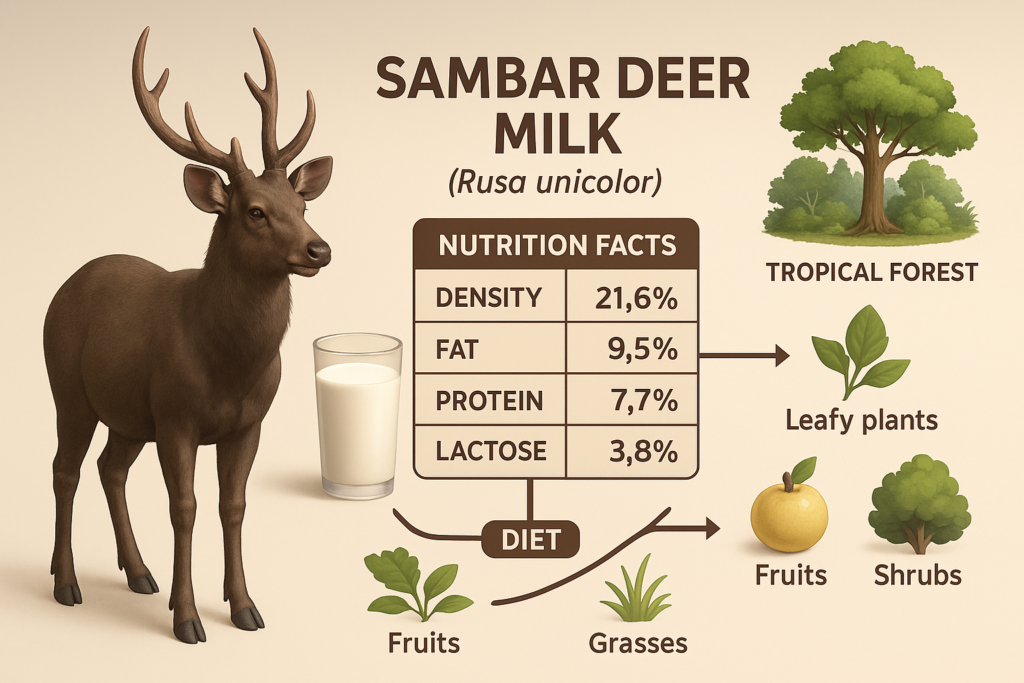

Scientific data on sambar deer milk comes primarily from wildlife rehabilitation centers, forest departments and zoological studies. The milk emerges as a highly concentrated formula dominated by:

high fat content for long-lasting energy and thermal stability

strong protein architecture for muscle expansion

rich minerals supporting rapid bone development

bioactive compounds enhancing immunity in predator-dense forests

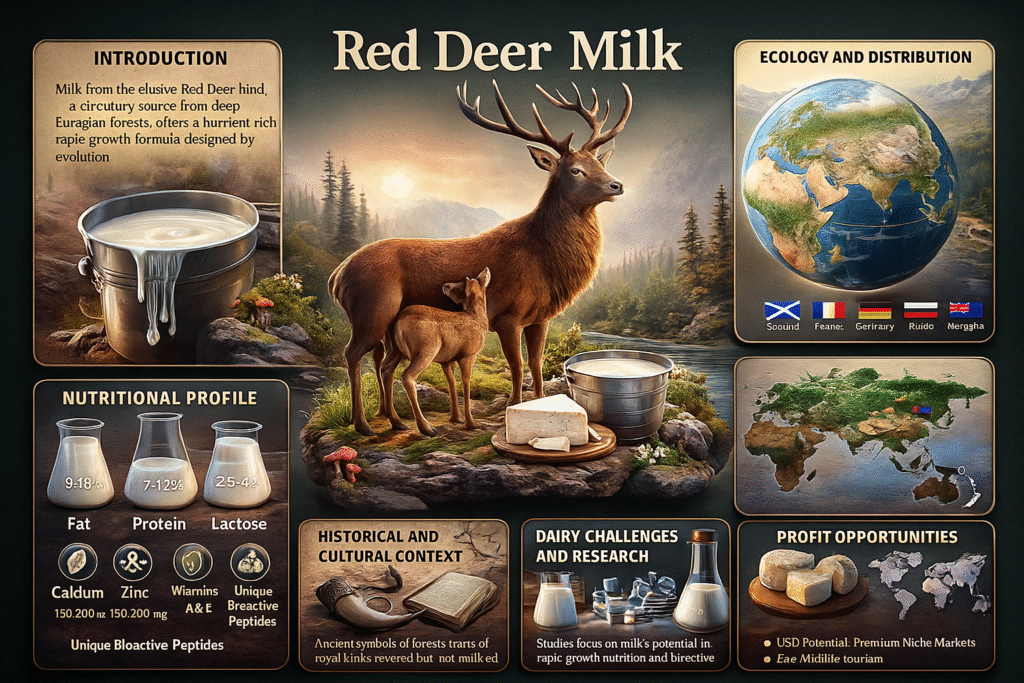

Although exact percentage ranges vary by region and season, researchers consistently note that sambar milk resembles the dense milk of red deer and is nutritionally stronger than cow milk. The fawn grows rapidly, becoming mobile within days and coordinated within weeks. This speed is only possible because the milk carries enough energy and protein to accelerate development.

Sambar milk is never watery. It is thick, creamy, almost heavy — evolution’s answer to survival.

- Ecology: How Indian and Southeast Asian Forests Shape Sambar Milk

The forests where sambar live determine the milk’s micronutrient density. In Indian dry deciduous forests, leaves and shrubs contribute minerals like calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. In Sri Lankan and Malaysian rainforests, the vegetation provides richer vitamin patterns derived from fruit-bearing trees and moist soil ecosystems. Himalayan foothill populations consume harsher grasses and mountain undergrowth, producing milk with slightly different mineral ratios.

Monsoon cycles shape diet, and diet shapes milk. Early monsoon milk becomes richer in vitamins. Late dry-season milk becomes more concentrated as the mother relies on body reserves.

Milk becomes a mirror of forest nutrition.

- Reproduction & Lactation: A Secretive, Intense Milk Economy

Sambar deer maintain solitary or loosely-structured social groups. The doe usually gives birth to a single fawn. Immediately after birth, the mother licks the newborn clean, hides it under bushes and moves only short distances while nursing. The fawn depends entirely on milk for several weeks, later adding vegetation in small amounts.

Lactation is intense but short compared to livestock. The milk composition changes quickly, beginning with colostrum rich in antibodies, then shifting into high-fat, high-protein milk as the fawn begins to explore. Because predators like tigers, leopards and wild dogs frequently cross sambar territory, the doe must ensure her fawn gains enough strength to follow her quietly and swiftly.

Milk makes that possible.

- Cultural History: Sambar in South Asian Human Narratives

Although sambar milk was never collected by humans, the animal itself appears widely in mythology and folklore. In India, classical texts mention sambar as a symbol of alertness and wilderness. Tribal communities in central India historically viewed sambar as a forest indicator, not as livestock. In Sri Lanka’s highlands, sambar became central to ecological traditions, often appearing at waterholes where entire ecosystems depend on their grazing patterns.

Milk remained unknown, untouched, never extracted — preserving its biological purpose entirely for the fawn.

- Scientific Research: What Sambar Milk Teaches Us

Milk from wild species reveals evolutionary logic. Sambar milk teaches researchers about:

rapid fawn muscle development required in predator zones

forest-driven mineral cycles

bioactive immunity compounds specific to tropical diseases

fat structures designed for irregular feeding intervals

Comparative studies between sambar, red deer and rusa deer show that tropical deer milk often contains higher antimicrobial peptides due to parasite-rich environments.

Sambar milk represents an evolutionary adaptation to heat, humidity and high predator density.

- Why Sambar Deer Cannot Be Dairy Animals

Milking sambar is biologically and ethically impossible:

the doe is highly sensitive to stress

milk let-down depends entirely on the fawn

separation causes immediate hormonal shutdown

milk yields are extremely small

the species is legally protected in many countries

Any forced attempt would endanger both the doe and fawn.

Thus the milk remains evolutionary, not agricultural.

- Taste Profile: What Scientists Have Observed

Very few humans have tasted sambar milk, mostly veterinarians during rehabilitation events. Descriptions mention a deep creaminess, faint forest aroma, and a densely textured richness. It resembles red deer milk but carries a slightly earthier profile due to tropical vegetation.

It is not meant for culinary use. Its purpose is singular build a forest runner.

- Global Distribution: Where Sambar Milk Exists in Nature

Sambar deer inhabit:

India

Sri Lanka

Nepal

Bhutan

Myanmar

Thailand

Malaysia

Indonesia

Across these regions, the milk varies with climate, elevation and diet, making sambar one of the world’s most geographically diverse deer milk species.

- Economic Relevance: What Value Sambar Milk Holds

Sambar milk cannot be sold or exploited, but its scientific value is high. Researchers study its protein structures to better understand tropical mammalian lactation. Conservationists examine milk composition to improve rehabilitation techniques. Wildlife ecologists use sambar growth rates to model predator-prey dynamics.

Indirect economic value appears through ecotourism, education programs and wildlife research.

- Future Outlook: Why Sambar Deer Milk Matters to Global Dairy Evolution

As dairy science expands beyond domestic species, sambar deer milk provides insights into:

tropical mammalian adaptation

wild nutritional efficiency

immune-supporting peptides

forest-driven mineral cycles

rapid-growth protein architectures

It represents a dairy profile shaped by heat, predators and dense vegetation — a unique addition to global dairy biodiversity.

- Conclusion: A Milk of Forest Strength and Evolutionary Precision

Sambar deer milk remains untouched by agriculture. It flows deep inside forests, seen only by the fawn, shaped by landscapes older than human culture. It is one of the densest, rarest and most biologically meaningful milks in Asia. Including it in your encyclopedia preserves a piece of natural dairy evolution rarely documented anywhere in the world.

- FAQs Sambar Deer Milk

Is sambar deer milk used by humans?

No it is inaccessible and belongs entirely to the fawn.

Why is sambar milk dense?

Because fawns must gain strength quickly in predator-heavy forests.

Which countries can study sambar milk?

India, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Malaysia.

Can sambar milk be commercially produced?

Never biologically impossible.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

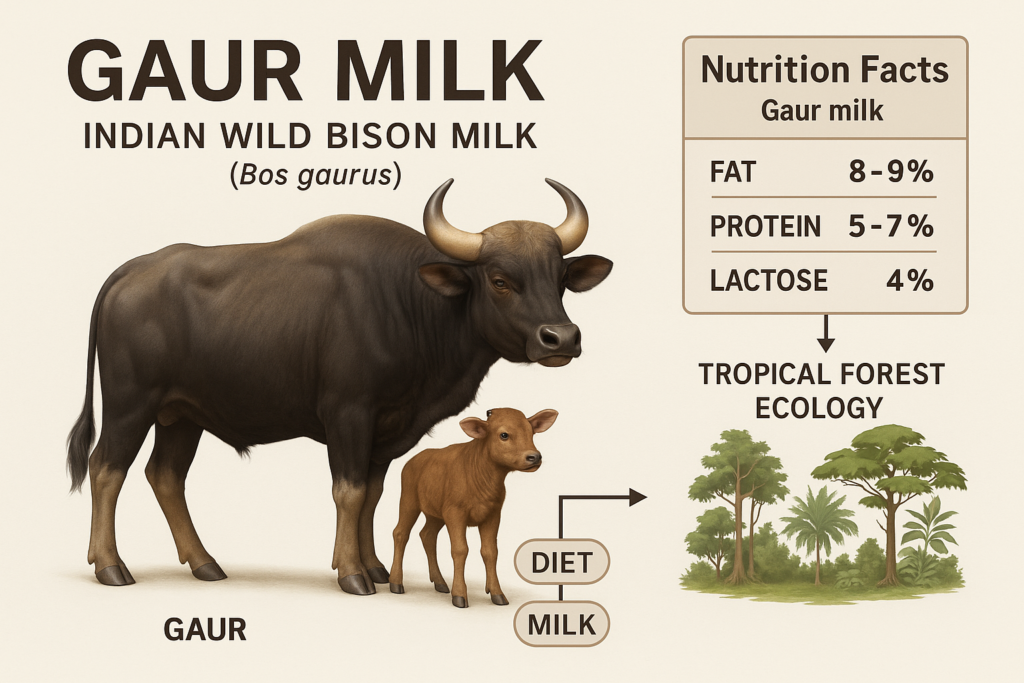

https://farmingwriters.com/gaur-milk-indian-wild-bison-complete-global-guide/