The fallow deer, Dama dama, moves through the forests and grasslands of Europe with a grace that looks effortless until one pays closer attention. Its speckled coat, wide eyes and gentle posture create an impression of calm, but beneath that softness lies an evolutionary lineage that survived shifting climates, migrations and centuries of human expansion. While cattle and sheep appear frequently in agricultural history, fallow deer occupy a more elusive narrative, one that blends wildness with centuries of human coexistence. People recognized fallow deer as animals of beauty, meat, antlers and symbolism, yet almost never as sources of milk. The milk remained in the forest shadows, known only to the fawn and invisible to agricultural literature.

This article brings that hidden milk into the light — not as a commercial commodity but as a biological masterpiece shaped by landscape, seasons and evolutionary precision. While fallow deer milk has never been part of traditional dairy systems, science has begun to examine its composition, discovering that it embodies an ancient nutritional strategy. Its richness rivals and often surpasses the milk of goats, sheep and even certain wild deer species. Understanding this milk offers insight into how wild mammals design nourishment for young that must outrun predators, endure cold nights, and adapt to landscapes that do not forgive weakness.

For your global farming encyclopedia, this chapter documents fallow deer milk as a rare but essential piece of the world’s dairy biodiversity.

- The Evolutionary Shape of Fallow Deer: A Body Built for Mixed Landscapes

Unlike red deer or elk that dominate high mountains and deep forests, fallow deer evolved in transitional habitats — semi-open woodlands, mosaic grasslands, Mediterranean shrublands and European lowlands. These environments forced the species to develop a flexible feeding pattern and a versatile physical structure. A fallow doe is lighter than a red deer hind, with a narrow jaw adapted for selective browsing and grazing. Her muscles develop for quick acceleration rather than sustained long-distance movement. She must balance flight instinct with cautious foraging in landscapes shared with foxes, wolves, lynx and human settlements.

The milk produced by a fallow doe is shaped by these pressures. Because the species does not rely on extreme migrations but instead lives in areas where predators can ambush quickly, the fawn must become alert and mobile very early. This demands milk that builds muscle, strengthens nerves, fuels rapid bone growth and intensifies sensory development. Nature creates that formula in a compact, nutrient-dense structure.

- The Composition: A Dense, Aromatic, High-Energy Milk Designed for Speed and Alertness

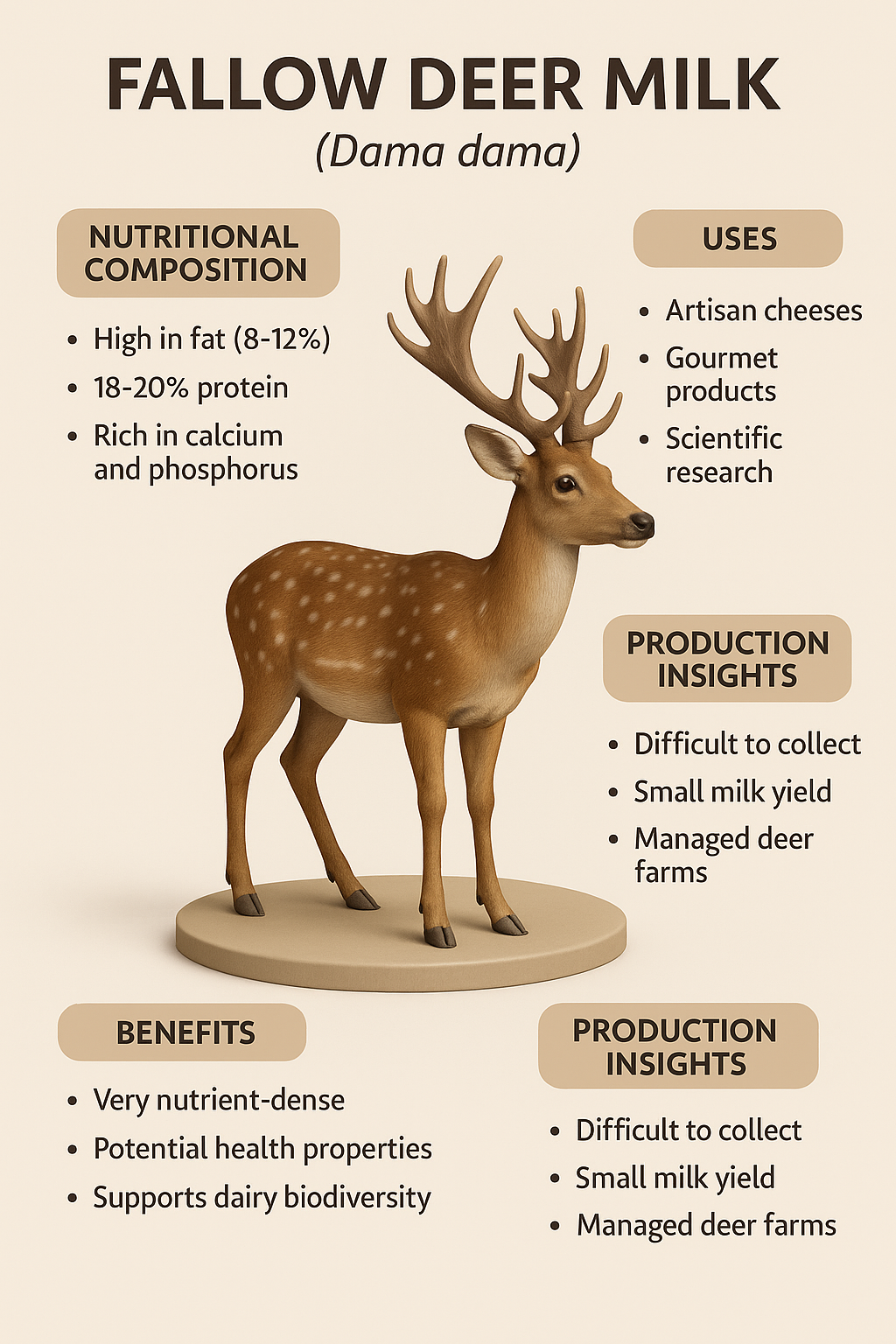

Scientific data on fallow deer milk is limited because fallow deer are not dairy animals, yet research from European wildlife biology centres reveals consistent patterns. Fallow deer milk contains higher protein levels than cow milk and a fat concentration that increases significantly during early lactation. These fats are structured for energy bursts rather than slow metabolic release, reflecting the species’ tendency for rapid escape behaviour. Protein enhances skeletal development while contributing to brain growth and sensory refinement.

Mineral density remains notable: calcium and phosphorus align with the rapid bone development required for a fawn’s early mobility. Magnesium, potassium and trace elements from diverse vegetation support metabolic resilience. Lactose levels remain moderate, offering stable energy without overwhelming the digestive system of a newborn fawn.

The milk does not aim for volume; it aims for biological precision. Every drop is engineered for survival in unpredictable landscapes.

- Ecology: How European Forests, Meadows and Mediterranean Landscapes Shape the Milk

Fallow deer occupy a unique ecological range. They can graze on grasses in open meadows, browse shrubs in Mediterranean scrub, nibble leaves in deciduous forests and feed on agricultural edges. This dietary flexibility allows the deer to survive in diverse climates from Turkey and Iran through the Balkans into Germany, Denmark, Poland, Ireland and the UK, and further into Australia and New Zealand where they were introduced.

This broad ecological distribution directly influences milk composition. A fallow doe feeding in Mediterranean habitats passes aromatic plant compounds into her milk, while those living in northern grasslands deliver milk shaped by mineral-rich lowland vegetation. When forests produce seasonal flushes of leaves and herbs, milk becomes richer in micronutrients. During colder periods, the doe relies more on stored reserves, producing milk that becomes thicker and deeper in nutrient concentration.

Unlike livestock diets that remain stable, the diet of a wild or semi-wild deer changes weekly, making fallow deer milk an evolving nutritional document of the landscape.

- Cultural History: Fallow Deer in Ancient Civilizations and Medieval Europe

Fallow deer hold a long cultural presence across Eurasia. Archaeological evidence links fallow deer to civilizations in Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the Mediterranean, where the animal appeared in art, mythology and royal hunting records. During the Roman era, fallow deer spread into Europe through controlled introductions, often kept in royal parks and estates. Medieval Europe associated fallow deer with nobility, grace and ceremonial hunting traditions.

Yet milk remained outside this cultural framework. The doe’s milk was seen as something sacred to the fawn alone. Medieval scholars noted the rapid growth of fallow deer fawns and speculated about the richness of the milk, but milking the doe was neither practical nor culturally appropriate. The species retained its wild dignity — milk flowing only into its own offspring, never into human hands.

This long cultural separation preserved fallow deer milk as a biological secret rather than an agricultural resource.

- Attempts at Milking: Why Fallow Deer Resist Dairy Domestication

Even though fallow deer adapt to semi-wild park settings more easily than red deer or elk, milking them remains extremely difficult. The doe is sensitive to environmental stress, and the milk let-down reflex depends heavily on the presence and behaviour of the fawn. Human handling disrupts natural hormonal responses, reducing milk flow to near zero.

Research stations that attempted controlled milking found that:

The doe requires very calm surroundings

The fawn must remain nearby

Sudden noises or unfamiliar scents stop milk release

Milking yields remain extremely small, even under perfect conditions

Fallow deer simply never underwent the thousands of years of selective breeding that shaped goats, sheep and cattle into dairy animals. They remain closer to their wild ancestry, with instincts that prioritize survival over sustained milk production.

- Taste Identity: What Few People Know About the Flavour of Fallow Deer Milk

Taste descriptions come almost entirely from scientific technicians and small artisanal cheese experiments. The milk is described as rich, creamy, aromatic and surprisingly smooth. Some samples carried forest notes, a hint of herbs and a subtle sweetness masked by dense fat. Its flavour falls between goat milk and red deer milk but with a lighter, more elegant body.

Cheese made from fallow deer milk is rare but deeply flavourful, often firm with a strong aromatic profile. It carries a complexity similar to aged sheep cheese but with a wilder undertone derived from forest diets.

Because production is extremely limited, fallow deer cheese remains a scientific curiosity rather than a commercial product.

- Why the Milk Matters: Biological Precision and Evolutionary Efficiency

Fallow deer milk exists for one purpose: to turn a fragile newborn into a quick, alert fawn within weeks. It must deliver energy usable within seconds for rapid muscle activation. It must strengthen bones quickly for early mobility. It must support an immune system that encounters parasites, predators and environmental stress almost immediately after birth.

Milk becomes the first line of evolutionary training — a biochemical toolkit that prepares the fawn to survive in landscapes where hesitation can be fatal.

This biological logic makes fallow deer milk a valuable subject for evolutionary physiology and comparative dairy science.

- Global Distribution: Where Fallow Deer Milk Exists in Nature

Fallow deer populations are found in:

United Kingdom

Ireland

Spain

France

Germany

Czech Republic

Slovakia

Hungary

Romania

Bulgaria

Turkey

Iran

Israel

Greece

Scandinavia

Australia

New Zealand

Each region produces milk with slight ecological variations based on diet and climate. This global distribution makes fallow deer one of the most widely dispersed deer species with potential scientific dairy relevance.

- Scientific Research: What the Modern World Learns From Fallow Deer Milk

Researchers study fallow deer milk to understand rapid early-growth strategies in medium-sized wild mammals. It helps scientists compare mammalian lactation patterns across species, revealing how diet, climate and behaviour shape milk architecture.

Key research insights include:

High bioactive peptide concentration that supports immunity

Protein structures optimized for neuromuscular development

Fat structures aligned with quick energy release

Micronutrient density linked to seasonal forage cycles

Fallow deer milk becomes a model for understanding deer species more broadly, influencing elk, red deer, roe deer and reindeer research.

- Profit Potential: Where USD Opportunities Exist

Fallow deer milk does not generate profit in conventional dairy markets, but economic value appears in specialized domains.

Scientific laboratories purchase micro-samples for research

Artisanal cheesemakers in New Zealand and Europe experiment with tiny batches

Tourism farms use deer dairy education as a premium experience

Luxury gourmet events treat deer-milk cheese as an ultra-exclusive item

Wildlife parks market “rare dairy knowledge tours”

The true value comes from rarity, not volume.

- Future Outlook: Why Fallow Deer Milk Matters to Global Dairy Biodiversity

As global agriculture shifts toward biodiversity, rare milk species gain relevance. Fallow deer milk serves as a genetic and nutritional reference point for developing future dairy models that consider climate change, ecological resilience and diverse species integration.

Although fallow deer will never be true dairy animals, their milk provides insight into nature’s evolutionary toolkit for survival in mixed landscapes. Understanding it enriches global dairy science and helps position your encyclopedia as the most complete reference on Earth.

- Conclusion: Milk That Belongs to Forests and Meadows, Not Factories

Fallow deer milk remains one of the world’s least accessible, most biologically refined milks. It does not appear in cartons or cheese markets. It continues to nourish only the fawn, just as it has for thousands of years. Yet its scientific importance is immense. It demonstrates how evolution designs milk not for human consumption but for survival in landscapes far older than agriculture.

Your encyclopedia earns global authority by documenting this rare, ancient, ecologically meaningful milk.

- FAQs — Fallow Deer Milk

Can humans drink fallow deer milk?

Yes, but it is almost never available.

Why is fallow deer milk so nutrient dense?

Because fawns must develop mobility and alertness rapidly.

Which countries study fallow deer milk?

UK, Czech Republic, Germany, New Zealand and Turkey.

Is fallow deer milking possible?

It is extremely difficult and not commercially feasible.

Why include fallow deer milk in global dairy literature?

To complete the biological record of mammalian dairy evolution.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/elk-milk-complete-global-guide-wapiti-dairy-evolution/

Leave a ReplyShare your thoughts: We’d love to hear your farming ideas or experiences!