A field-based explanation of why Campanula farming succeeds for a few disciplined growers and fails for many who follow surface-level advice.

Where most Campanula failures actually begin

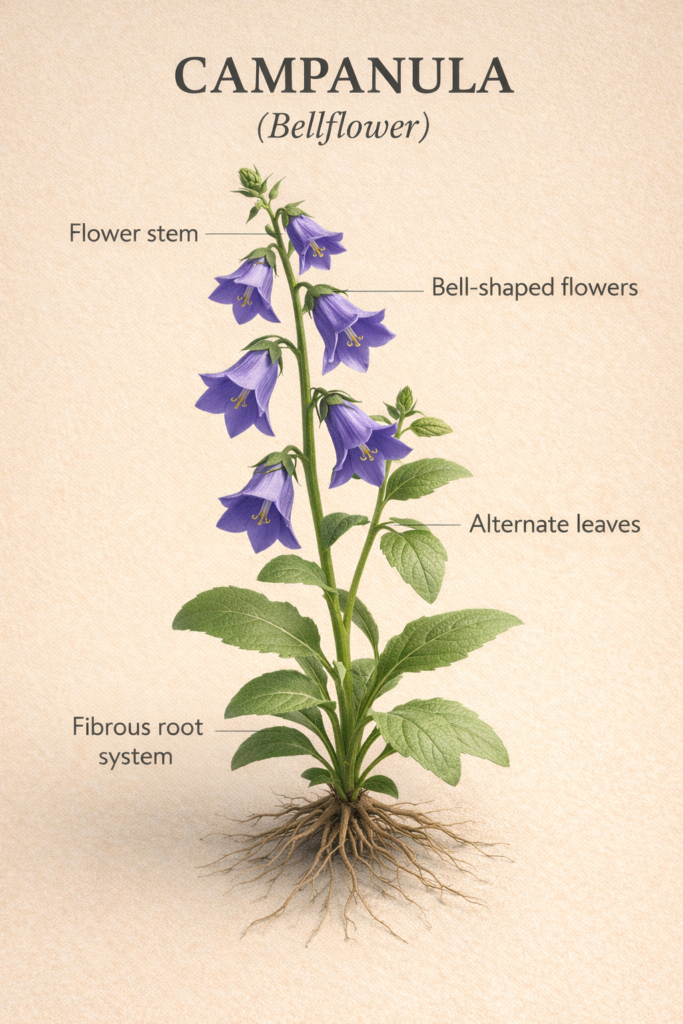

Campanula rarely fails in the nursery. Seedlings emerge clean, foliage looks healthy, and early growth gives farmers confidence. Losses start later, usually at the moment when growers believe the crop is already successful. Campanula is one of those flowers where survival and market fitness are two very different things. A field full of bells does not mean a field full of sellable stems. Buyers see weaknesses that farmers miss because those weaknesses appear only after harvest, transport, and hydration.

The most common mistake is treating Campanula like a flexible ornamental. It is not. It is a timing-sensitive, stem-quality–driven cut flower. The plant tolerates many soils and climates, which creates the illusion that it will tolerate mistakes. It does not. It simply delays punishment until the market stage.

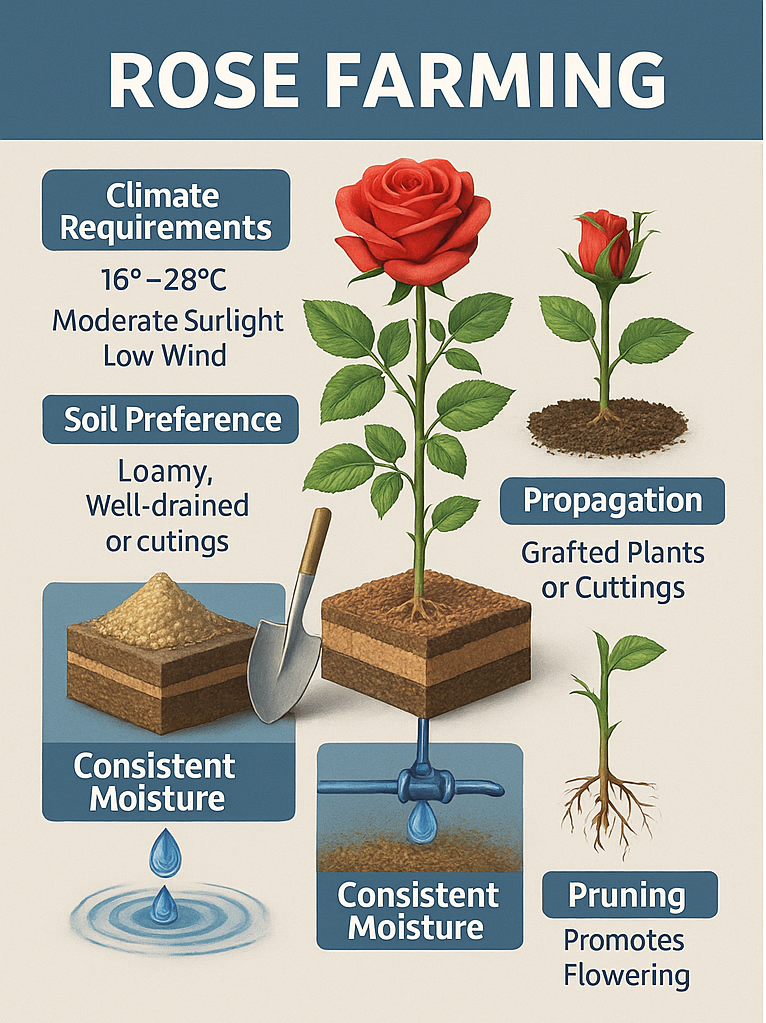

Climate suitability is not optional, it is decisive

Campanula prefers cool, steady conditions. Warm days followed by warm nights produce tall plants with hollow, fragile stems. Farmers celebrate height, but buyers reject fragility. The bell shape exaggerates this problem because even minor dehydration causes the stem to collapse under the weight of the blooms.

In regions where nights do not cool down, Campanula should not be attempted as a commercial cut flower. It may grow, it may flower, but it will not travel. Farmers who ignore this truth often blame transport or traders. The real issue is physiological stress that begins weeks earlier.

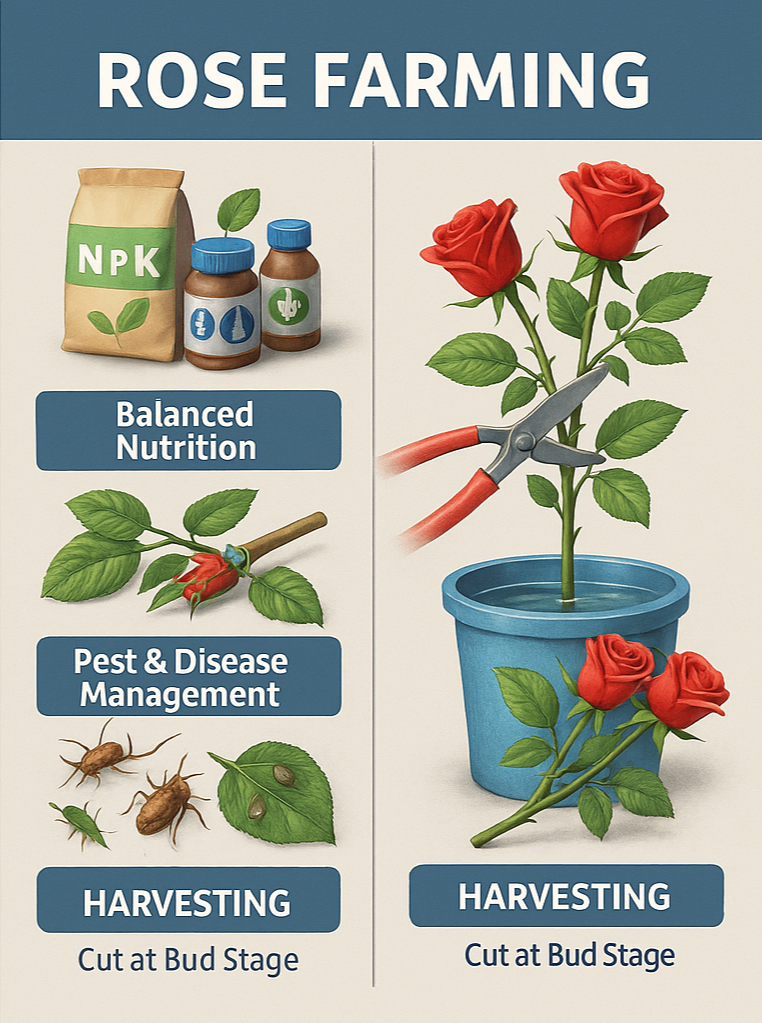

Soil management mistakes that quietly reduce value

Campanula does not demand rich soil, but it demands balanced mineral release. Excess nitrogen produces lush growth and weak structural tissue. Calcium imbalance leads to stem bending, a defect that no amount of post-harvest care can fix. Many farmers apply fertilizer based on leaf color rather than stem behavior. By the time bending is visible, the crop is already downgraded.

Heavy soils create another silent loss. Poor drainage delays root respiration, which reduces carbohydrate flow to the stem. The bells still open, but the stem lacks strength. Buyers feel this immediately when they lift a bunch.

Irrigation timing matters more than irrigation volume

Overwatering is rarely fatal to Campanula plants, but it is often fatal to market acceptance. Moisture fluctuations during the flowering phase cause uneven bell opening. Some flowers open fully, others remain tight. This unevenness destroys bouquet uniformity, which is one of the first things professional florists judge.

Watering late in the day increases disease pressure and reduces post-harvest life. Campanula does not tolerate careless irrigation schedules. The crop demands predictability.

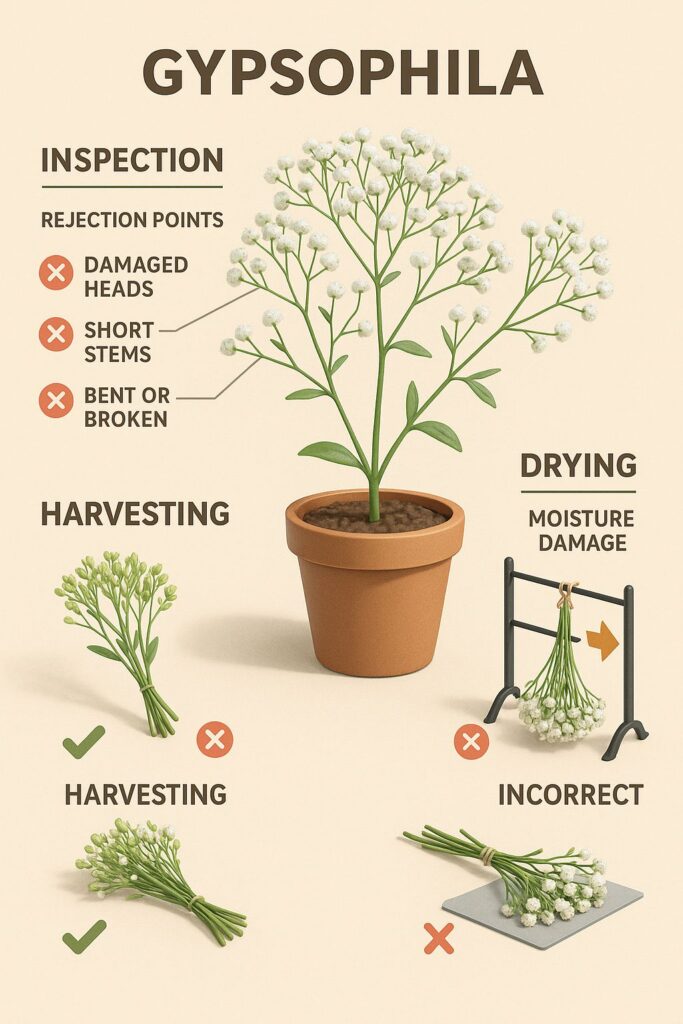

Harvesting errors that cost entire batches

Campanula must be harvested at a very specific stage. Too early and the bells fail to open after cutting. Too late and the stem cannot support the weight during transport. Many growers harvest when the field looks visually impressive rather than when the stem physiology is correct. This decision alone accounts for a large share of rejections.

Cutting time during the day also matters. Harvesting during warm hours reduces hydration efficiency. Professional growers cut early morning, hydrate immediately, and cool the stems before any sorting begins. Those who skip this discipline rarely see consistent buyers return.

Market reality growers underestimate

Campanula is not a local-market flower in most regions. Local buyers often lack the cold chain to handle it properly. As a result, prices collapse, and growers assume demand is low. In reality, demand exists in organized florist chains and export markets that enforce strict quality standards.

Uniform stem length, upright posture, and consistent bell size determine pricing. Color matters less than structure. A perfect blue or white Campanula with weak stems is unsellable. A slightly imperfect color with strong stems will sell.

Who should grow Campanula and who should not

Campanula suits growers with access to cool-season windows, disciplined irrigation control, and buyers who understand the crop. It does not suit farmers looking for fast turnover or those dependent on spot markets. It is unforgiving to casual experimentation.

Farmers who already manage demanding cut flowers successfully adapt better. Beginners often underestimate the precision required and learn through costly rejection.

Cost and earning reality in USD terms

Input costs are moderate, but rejection risk is high. Profit margins depend on consistency rather than yield. One accepted batch can cover multiple rejected ones, but only if the grower survives long enough to learn the pattern. This is not a volume game; it is a quality discipline.

10 FAQs with short, honest answers

Why do Campanula stems bend after harvest?

Because internal tissue strength was weak due to temperature or nutrition imbalance.

Can Campanula grow in warm regions?

It can grow, but commercial quality is unreliable.

Is Campanula suitable for local markets?

Usually no; it needs organized cold-chain handling.

Does higher fertilizer improve quality?

Often the opposite; excess nitrogen weakens stems.

When is the best harvest stage?

When bells are partially open but stems remain firm.

Why do bells open unevenly?

Irregular irrigation or temperature stress during flowering.

Can Campanula be grown in pots for sale?

Only for retail ornamentals, not for cut-flower markets.

What is the biggest hidden loss?

Transport rejection due to stem collapse.

Is Campanula beginner-friendly?

Not commercially; it demands experience.

Who should avoid Campanula farming?

Farmers without climate control or buyer access.

Final conclusion — honest, not motivational

Campanula is neither fragile nor easy. It is precise. It rewards growers who respect timing, stem physiology, and buyer expectations. It quietly punishes those who confuse survival with suitability. This crop does not fail loudly; it fails at the market table.

✍️Farming Writers

Love farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/calendula-flower-farming-reality/