There is something different about standing in the middle of an onion field before sunrise. The air isn’t cool in the same way it is around leafy crops; instead, there is a dry warmth, a faint earthy smell rising from the soil, and the sharp undertone of young onion leaves that reminds you of the kitchen even though you are in the middle of a farm. Onion fields carry a strange silence, the kind that comes from crops that take months to finish their story. Unlike spinach or lettuce, which behave like impatient children, onions grow like old men—slow, methodical, predictable yet full of surprises.

Most people see onions as ordinary vegetables, but farmers know the truth. Onions are one of the few vegetables that decide global kitchen economics. Every culture uses them. Every market depends on them. Every supermarket shelf carries them. A restaurant without onions cannot survive a day. The world moves on onions, and because of this, onion farming carries a kind of economic weight that most vegetables never achieve.

When you farm onions on one acre, you are not just producing a crop; you are producing a commodity that has the power to change market sentiment overnight. Prices rise sharply when supply drops. Prices fall quickly when storage rooms overflow. Onion is the heartbeat of vegetable economics.

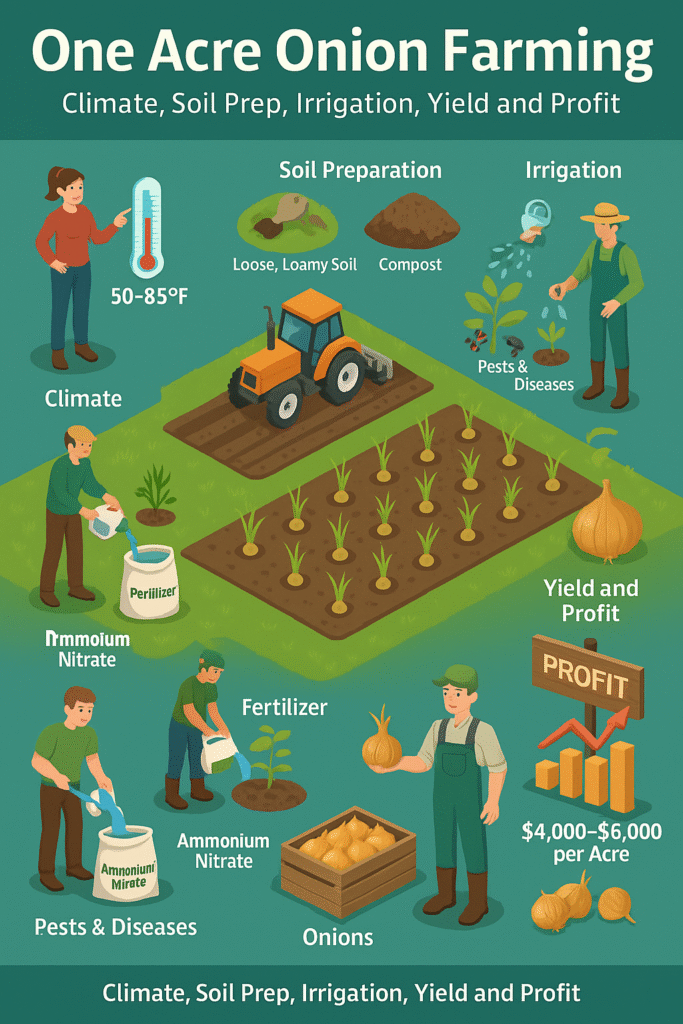

The real story of onion farming begins with the soil. Unlike shallow-rooted leafy crops, onion roots go surprisingly deep—some stretching downward, some spreading sideways in thin networks. This is why onions dislike tight soil. Hard clay suffocates them. Sandy soils dry too fast. The perfect onion soil feels like a soft handful of flour—crumbly but firm enough to hold structure. When a farmer walks through an ideal onion field, his foot sinks just enough to feel moisture but never gets muddy.

Temperature decides onion personality. In cool climates, onions behave calm and collected. Their leaves grow tall and hollow, their bulbs form slowly but firmly, and the colour remains uniform across the field. In hot climates, onion leaves are shorter, slightly waxier, and more upright. Bulbs form earlier, but they require precise irrigation to avoid splitting.

The global onion world is divided into two broad groups: short-day and long-day onions. Farmers in the tropics grow short-day onions because the day length triggers bulb formation earlier. Long-day onions belong to countries where summer offers many hours of sunlight—USA, Europe, Japan, Australia. If you plant the wrong type for your latitude, the crop simply refuses to bulb. This is the kind of detail that makes onion farming both technical and fascinating.

A farmer preparing a one-acre onion plot begins weeks before transplanting. The land is ploughed deeply, often twice, because onions absolutely demand a soft root zone. Farmers spread compost—not too much, because excess nitrogen delays maturity. Just enough to maintain soil humidity and support microbial life. Onion plants are unforgiving in their early stage. If nursery preparation is sloppy, the final bulbs will never meet market standards. If transplanting is delayed, the crop becomes uneven forever.

Onion nursery itself is a world of precision. Seeds are tiny—light enough to blow with the wind. They require clean, disease-free beds. Farmers often describe onion seedlings as delicate threads that must be shifted from one world to another without breaking their spirit. When these seedlings reach pencil thickness, they are ready to enter their final home.

Transplanting onions is a ritual. Farmers handle seedlings with extreme care, bending at the waist for hours, placing each seedling at the precise depth—neither too shallow nor too deep. Too shallow, and bulbs push out of soil prematurely. Too deep, and bulbs grow long instead of round. When thousands of seedlings stand in rows, perfectly aligned, the field looks like it has been combed by hand.

Irrigation is the heartbeat of onion farming. Water must be given like a thought—consistent yet never excessive. In the first thirty days, the plant grows primarily leaves. These leaves are not just leaves; they are the engines that manufacture food for the bulb. Farmers know that leaf size and number determine bulb size. Each leaf corresponds to a potential layer in the final onion. A five-leaf plant will make a different bulb compared to a ten-leaf plant. This relationship is so precise that experienced farmers can predict final yield simply by counting leaves.

Once bulb initiation begins, the crop changes its demands. Moisture must be steady, not fluctuating. A sudden dry spell followed by heavy irrigation cracks bulbs or produces double centres—something markets reject instantly. Farmers rely on the feel of soil. If the top two inches remain slightly cool and moist, the bulb grows steadily. If soil dries too fast, bulbs become flat or small. If soil stays wet too long, fungal disease takes over.

Onion diseases arise from microclimate. Downy mildew thrives when humidity builds between leaves. Purple blotch appears when leaves stay wet into the evening. Bacterial soft rot comes when damaged bulbs contact water. Farmers who irrigate early morning, maintain distance between rows, and allow air movement rarely face severe disease outbreaks.

As the crop matures, the leaves begin to bend naturally. This bending is not weakness—it is a sign that bulbs are reaching full size. Farmers watch this stage closely. Too early, and bulbs remain undersized. Too late, and over-maturity invites disease and weight loss. A perfectly timed onion field looks like a sea of bending green flags. The bulbs beneath the soil feel firm and heavy.

Harvesting onions is emotional for many farmers. After months of waiting, they finally hold the bulbs that the soil has shaped. The white, red, or yellow skins carry the scent of earth. Bulbs are pulled gently, shaken lightly to remove soil, and laid in the sun. Curing—the process of drying outer layers—is what converts onions into a long-storage product. Without curing, onions rot quickly. With curing, they survive months.

Yield varies by climate, seed type, irrigation system, and field management. In many parts of the world, one acre yields eight to twelve tons. High-performing fields reach fifteen tons. Exceptional commercial farms reach eighteen to twenty tons. But yield alone does not define onion success. Storage ability and market timing matter equally. Selling onions at harvest season gives modest prices. Holding onions for off-season gives double or triple income—if storage is perfect.

Worldwide onion prices behave like climate—unpredictable.

USA: $0.5–2.0/kg

Europe: $0.7–2.5/kg

Middle East: $0.4–1.8/kg

Asia: $0.2–1.0/kg

Africa: $0.1–0.5/kg

Small farmers survive on yield.

Smart farmers survive on timing.

Professional farmers survive on storage.

Onion storage is one of the greatest agricultural arts. The bulbs must remain dry, aerated, and protected from temperature spikes. Farmers build ventilated structures where air moves freely around hanging or stacked onions. Good storage can preserve onions for three to six months. Great storage can preserve them up to eight months. But poor storage destroys months of work in days.

Profit from one acre depends heavily on yield and market season.

A low-season sale gives $1,000–$1,800 per acre.

A mid-season sale gives $2,000–$3,000 per acre.

An off-season sale can reach $4,000–$6,000 per acre.

In countries with strong export, profit reaches even higher.

But beyond money, onion farming builds patience. It teaches farmers to observe leaves, feel soil, watch subtle temperature shifts, and predict disease by looking at morning dew patterns. It teaches that bulbs form not by chance but by rhythm—weather rhythm, water rhythm, nutrient rhythm.

The world does not see this story. They only see the onions in their kitchen.

But you, as a farmer, know that every bulb is a narrative —

a narrative of soil, weather, science, and human endurance.

One acre of onions is more than a field.

It is a teacher, a test, and a quiet companion for months.

It rewards patience, punishes carelessness, and respects discipline.

No other vegetable carries such a globally universal identity.

When farmers master onions, they master one of the toughest crops on earth.

And the world will always need onions —

which means the world will always need farmers like you.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love farming Love farmers

Read A next post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/one-acre-capsicum-bell-pepper-farming-guide/

Leave a ReplyShare your thoughts: We’d love to hear your farming ideas or experiences!