Licorice, known scientifically as Glycyrrhiza glabra, is a root that has fascinated healers, traders, and scientists for centuries. It is one of those rare plants that combine medicinal value with unique sweetness. The root’s natural compound, glycyrrhizin, is fifty times sweeter than sugar, yet it comes with additional benefits anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immune-modulating properties that make it a cornerstone of traditional medicine systems across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. The global herbal industry, confectionery manufacturers, beverage companies, and pharmaceutical firms all rely on licorice for its distinctive flavor and medicinal potency. This extraordinary versatility has turned licorice farming into a globally significant and economically rewarding enterprise.

Licorice grows naturally across temperate regions of Asia and Europe. Its native zones stretch from the Mediterranean basin to Iran, India, China, and parts of southern Europe. Over centuries, cultivation expanded to regions like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey, Russia, and Central Asia. Modern commercial farms also exist in the United States, Egypt, and parts of Africa. The plant’s adaptability to semi-arid climates with well-drained soils makes it a valuable crop even in regions unsuitable for high-rainfall agriculture.

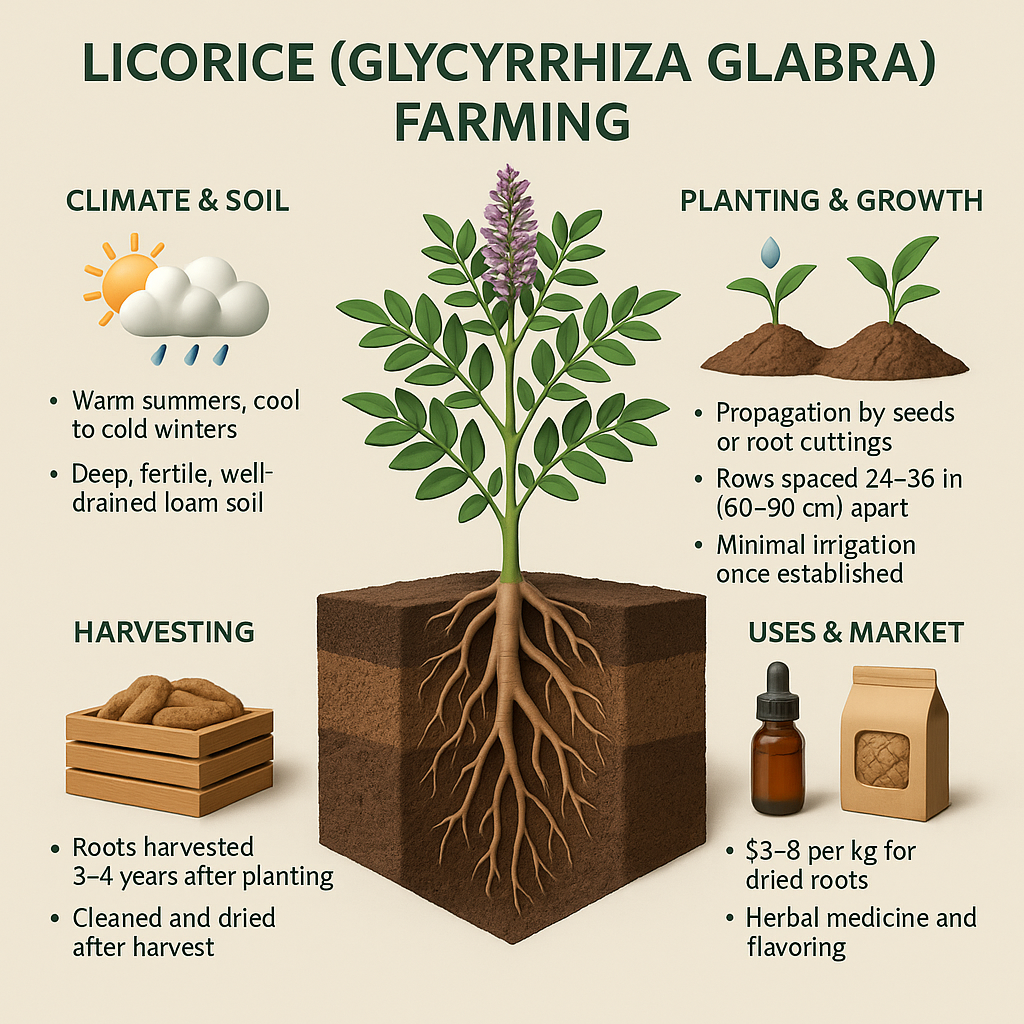

Licorice is a hardy perennial legume that develops a network of long, horizontal underground rhizomes and vertical roots. These roots store the valuable glycyrrhizin compound that defines licorice’s commercial worth. In favorable conditions, a single plant can live for several years, continuously regenerating from underground structures. Farmers usually cultivate it for three to four years before harvesting for commercial extraction. The crop thrives best in temperate to semi-arid zones where summers are warm and winters are cool enough to induce dormancy.

The ideal climate for licorice combines warm growth seasons with cold winters. The crop tolerates high summer temperatures up to forty degrees Celsius, provided there is adequate soil moisture. However, prolonged waterlogging or humid tropical climates damage the roots. Cold winters allow the plant to rest and redirect energy into root thickening. The growing period typically spans from spring to autumn, after which the above-ground stems dry naturally, leaving the underground root network rich and fibrous.

Soil selection plays a defining role in the success of licorice farming. The plant prefers deep, fertile loamy or sandy loam soils with excellent drainage. Heavy clays restrict root penetration and lead to water stagnation, which causes rot. Licorice’s deep taproots penetrate up to one and a half meters, so the soil must be loose and aerated. Slightly alkaline to neutral pH levels, between six point five and eight, provide optimal conditions. Farmers enrich soil with organic manure or compost before planting to ensure microbial activity and humus content, mimicking the natural riverbank environments where licorice often grows wild.

Land preparation for licorice farming begins with deep ploughing to break the subsoil and improve drainage. Large roots or stones must be removed because they obstruct rhizome expansion. Beds are leveled and raised slightly in areas prone to heavy rain. Before planting, farmers apply organic matter and allow the soil to settle for a few weeks. Licorice is a long-duration crop; hence, early land preparation defines years of performance.

Propagation in licorice farming can occur through seeds, rhizome cuttings, or root segments. However, seed germination tends to be slow and irregular due to hard seed coats. Farmers scarify seeds gently or soak them in warm water for twenty-four hours before sowing. Rhizome cuttings and root fragments, on the other hand, offer faster establishment and uniform growth. A segment of root about fifteen centimeters long with one or two buds can produce a new plant under favorable conditions. This vegetative propagation ensures genetic consistency and quicker field coverage.

Planting usually takes place in early spring after frost danger passes. In temperate climates, licorice cuttings are planted in rows spaced sixty to ninety centimeters apart, with plants twenty-five to thirty centimeters apart within the row. Deep planting encourages strong taproot formation. The field must remain weed-free during the initial months because young licorice plants grow slowly. As they mature, they form dense foliage that naturally suppresses weeds.

Irrigation requirements depend heavily on soil type and climate. Licorice grows best under moderate moisture, never in waterlogged conditions. During establishment, regular watering ensures deep root penetration, but once the plants mature, they can withstand moderate drought. In commercial systems, furrow or drip irrigation provides the right balance between moisture and aeration. Excessive irrigation reduces glycyrrhizin content and leads to root diseases. Thus, farmers prefer alternate irrigation cycles that mimic natural rainfall.

Nutrient management focuses on building soil fertility organically. Since licorice belongs to the legume family, it naturally fixes atmospheric nitrogen through root nodules. Therefore, external nitrogen input remains minimal. However, phosphorus and potassium play key roles in root development and secondary metabolite synthesis. Farmers incorporate organic compost, bone meal, and rock phosphate at planting. Periodic top-dressing with compost tea or liquid organic fertilizers enhances soil microbial life and strengthens plants against stress.

Pest and disease management in licorice farming is relatively simple compared to many other crops. The plant shows natural resilience due to its bioactive compounds. However, fungal root rot, leaf spots, and stem borers can appear in humid conditions. Preventive measures include proper spacing, well-drained soil, and crop rotation. Farmers avoid chemical pesticides to preserve medicinal integrity, opting instead for neem extracts and biological pest control agents.

The growth cycle of licorice extends over several years. During the first year, the plant focuses on establishing strong roots and rhizomes. Above-ground stems remain small. In the second year, vigorous shoot growth appears, accompanied by extensive underground expansion. By the third or fourth year, roots reach harvestable size and medicinal potency. Root harvesting requires patience and precision. Farmers dig deep trenches using spades or mechanical diggers, lifting long roots carefully to avoid breakage. After harvesting, roots are washed, sorted, and dried in shade to preserve glycyrrhizin and other essential compounds.

Processing involves cutting dried roots into small pieces or grinding them into powder. For industrial extraction, roots undergo pulverization and solvent extraction to isolate glycyrrhizin and other active constituents. Food and beverage industries use processed licorice powder as a flavoring agent, while pharmaceutical companies employ concentrated extracts in cough syrups, anti-inflammatory medicines, and digestive formulations. The demand for licorice also extends into natural cosmetics, tobacco, and confectionery sectors, ensuring a broad and stable global market.

Global market dynamics for licorice continue to strengthen. China, India, Iran, Afghanistan, and Italy lead global supply, but Europe and North America remain major importers. Natural health products, herbal supplements, and sugar-free formulations have dramatically increased global consumption. Average prices for licorice roots vary between three and eight USD per kilogram for bulk dried roots, while purified extracts and powder fetch up to thirty USD per kilogram. With rising herbal wellness awareness, the market continues to expand annually.

Economic analysis of licorice farming reveals strong long-term profitability. While initial investment is moderate, the crop provides multiple years of yield from a single planting due to rhizome regeneration. Even after harvest, residual roots sprout again when managed properly. This regenerative feature reduces replanting costs. Once established, licorice fields require minimal maintenance, and income streams remain steady due to consistent demand. Farmers who integrate organic certification further increase profit margins by accessing premium export markets.

Sustainability forms the foundation of modern licorice cultivation. Because the plant enhances soil nitrogen naturally, it supports sustainable crop rotation systems. Its long-term root structure also prevents soil erosion and improves underground microbial ecosystems. Organic farming practices, shade management, and low-input systems make licorice an environmentally sound medicinal crop.

In conclusion, licorice farming blends ancient wisdom with modern agricultural science. It symbolizes patience, sustainability, and long-term profitability. With the world turning increasingly toward natural health and plant-based wellness, licorice remains one of the most powerful opportunities in global herbal farming. This human-written, deeply detailed guide offers a complete understanding of how to cultivate, process, and market licorice for world-class profitability and ecological harmony.

FAQ FOR LICORICE FARMING

New farmers often ask how long it takes for licorice roots to mature. The typical period is three to four years before harvest, but older plants produce thicker, higher-quality roots. Another common question concerns climate; licorice thrives in semi-arid temperate climates with warm summers and cool winters. Soil suitability often comes up as well — the crop demands deep, fertile, well-drained loamy soil. Farmers also ask about irrigation, and licorice requires moderate water only during establishment, then survives well on natural rainfall. Finally, many growers wonder about profitability, and licorice remains one of the most profitable medicinal crops because of its wide market applications and stable international prices.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers