The mistake that creates “many potatoes but no money”

Potato farmers across Asia, Europe, and Africa often say the same line:

“My field produced a lot, but money was low.”

The hidden reason is almost always plant spacing.

Potato plants can survive very close spacing.

Tubers cannot.

When plants are crowded, the plant keeps growing leaves, but tuber formation gets divided into many small pieces instead of fewer large ones. Buyers don’t pay for count. They pay for grade.

Why tight spacing feels right — but fails later

Farmers use close spacing because:

Land feels fully used

Early canopy looks strong

Weed pressure reduces

But underground, something else happens:

Stolons collide early

Tubers compete for the same soil volume

Size expansion stops early

Skin remains thin and irregular

This is why crowded potato fields give:

Too many small tubers

High sorting loss

Low storage value

The spacing–tuber size relationship

Potato does not increase size at the end.

Tuber size is decided early, within the first 30–40 days.

Once spacing restricts expansion, no fertilizer can fix it.

This is why spacing matters more than:

Seed size

Extra nitrogen

Late irrigation

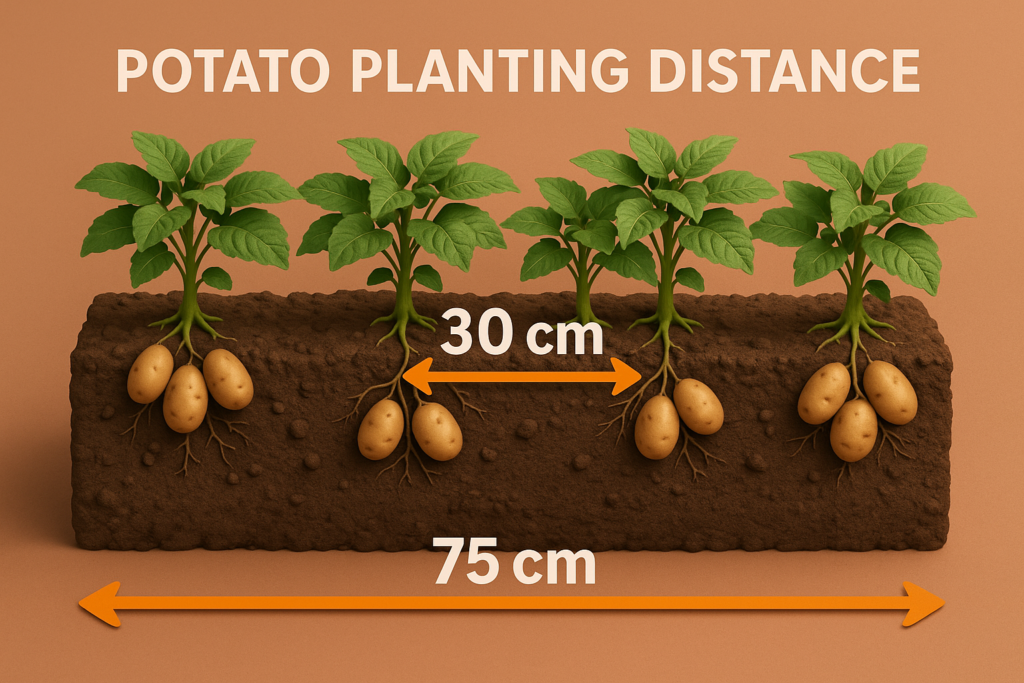

Field-proven spacing used by commercial growers

For table potatoes (fresh market):

Plant to plant: 20–25 cm

Row to row: 60–75 cm

For processing potatoes (chips, fries):

Plant to plant: 25–30 cm

Row to row: 75–90 cm

Wider spacing allows:

Fewer but larger tubers

Better skin finish

Uniform grading

Higher price per kilogram

Why “more plants” reduces total sale weight

This is the hardest truth for farmers to accept:

More plants = more tubers

More tubers = smaller size

Smaller size = rejected or low-priced harvest

Net result:

Total harvested weight may look similar, but marketable weight drops sharply.

Who should NOT follow wide potato spacing

Wider spacing is not ideal if:

You sell seed potatoes by count

You harvest very early baby potatoes

You grow only for home consumption

For commercial table and processing markets, spacing is non-negotiable.

Real farmer questions

Q1. Can I reduce spacing if soil is very fertile?

No. Fertility increases foliage, not tuber space.

Q2. Does variety change spacing rules?

Slightly, but tuber expansion limit remains the same.

Q3. Why do my potatoes look healthy but stay small?

Because leaf health hides underground competition.

Final judgment

Potato farming fails quietly underground.

Crowded fields reward leaves, not tubers.

If your harvest needs heavy sorting, spacing not seed is the real problem.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love farming Love Farmers.

Read A Next Post 👇