Farmers often fall for Foxglove because of its height, color range, and the way it stands upright like a structured spike demanding attention in any garden bed. But what most growers do not realise until after their first failure is that Foxglove does not forgive wrong timing. It behaves less like a typical ornamental and more like a crop that punishes impatience. Many farmers enter this cultivation assuming “if it grows in Europe’s wild hills, it will manage fine anywhere.” That belief alone destroys more Foxglove fields than pests ever will. The plant was shaped by cold winters, acidic soils, damp air, and slow sunlight rhythms — remove any one of these and the crop’s physiology collapses, no matter how beautiful the seeds looked on paper.

Professional growers who sell to premium florists learned long ago that Foxglove is not about quantity. Buyers are extremely particular. They reject stems that bend even slightly, spikes that bloom unevenly, or colors that wash out from heat stress. A farmer can spend months raising perfect rosettes, only to watch the entire stand collapse in a single warm spell because the plant was never designed to handle tropical nights. This mismatch between expectations and biology is exactly why Foxglove becomes a loss-making crop for those who treat it like a normal flower rather than a cool-season specialist.

The first decision a farmer makes — whether Foxglove suits their climate — determines 60 percent of the outcome. Soil type, fertilizers, spacing, irrigation — all these matter, but none can compensate for warm nights or poorly timed sowing. Experienced growers begin not with soil tests, but with temperature charts. They check if night temperatures drop below 15°C during the vegetative phase. When they don’t, they simply walk away from the crop for that year. Foxglove prefers restraint, not courage. And that restraint is exactly what separates profitable growers from those who struggle.

Another point farmers misunderstand is that Foxglove is technically a biennial in most climates. The first year gives leaves, the second gives flowers. But in countries where winters are mild, the plant behaves unpredictably — sometimes flowering early, sometimes refusing entirely. Farmers who try forcing the plant into bloom with fertilizers only worsen the problem. The deeper reality is that Foxglove times itself according to cold exposure, not calendar dates. If the winter fails, the flowering rhythm becomes unreliable. This is why large-scale growers either simulate winter through controlled nurseries or simply rely on cold-zone farms to maintain consistent quality.

Market behaviour around Foxglove is equally misunderstood. Local markets rarely pay high prices for it because customers don’t know the flower. Only professional florists, event decorators, and export chains value it. Their orders are strict: straight stems, tall uniform spikes, fully developed bells, and no leaf stripping scars. A farmer entering Foxglove farming without having a buyer ready is already halfway into a poor season. Unlike marigold or chrysanthemum, Foxglove is not a mass-market crop. It is a designer flower. And designer flowers punish those who produce blindly.

Soil does matter — but only when the grower has first respected the climate. Foxglove prefers acidic soil, something many regions simply do not offer. Farmers who ignore this and rely solely on compost find the crop producing coarse leaves but weak flowering. The spike begins developing but stops midway, creating a half-formed, unsellable stem. But when soil acidity is corrected early using elemental sulfur or acidic organic matter, the plant suddenly behaves like its European ancestors — disciplined, predictable, and beautifully structured.

Irrigation is the next frequent point of failure. Too little water during the rosette stage kills the core bud, and too much water rots the crown. Foxglove demands even moisture, nothing extreme. The worst mistake growers make is overhead irrigation on warm evenings. That single act invites fungal infections that hollow out the stem from within. Farmers discover the problem only on harvest day, when they cut the stem and it collapses. This is not a disease issue — it is an irrigation timing mistake.

Nutrient management is often overdone. Foxglove does not want heavy nitrogen. When nitrogen is excessive, the plant grows large rosettes that deceive growers into thinking the crop is healthy, but the spike remains short and weak. Balanced feeding with light phosphorus and potassium gives better spikes than any attempt to force growth artificially. Again, Foxglove punishes impatience.

Buyers care most about uniformity. A field that blooms in an uneven pattern loses half its sale potential. The farmer must stagger sowing or control cold exposure to achieve synchronized flowering. This is the one secret professional growers guard closely. They never sow all the seeds at the same time. They stagger batches by one to two weeks to identify which timing produces the best uniformity for that particular farm’s microclimate.

Harvesting, too, demands precision. A spike harvested too early will open poorly; harvested too late will drop bells in transit. Professional growers harvest when only one-third of the bells are open. This maintains structure during shipping. Local growers often harvest fully open spikes thinking they look more beautiful, but buyers reject them instantly because longevity collapses.

The economic truth of Foxglove farming is simple: Profit exists only when the grower produces for the premium market. Local mandis will never reward the effort. Export chains and high-end florists will. But they expect consistency and will not tolerate the excuses growers often make about climate surprises. In warm regions, Foxglove is better grown in controlled nurseries to avoid failure. In cool regions, field farming works easily. This difference is so fundamental that growers who ignore it repeat the same losses every season.

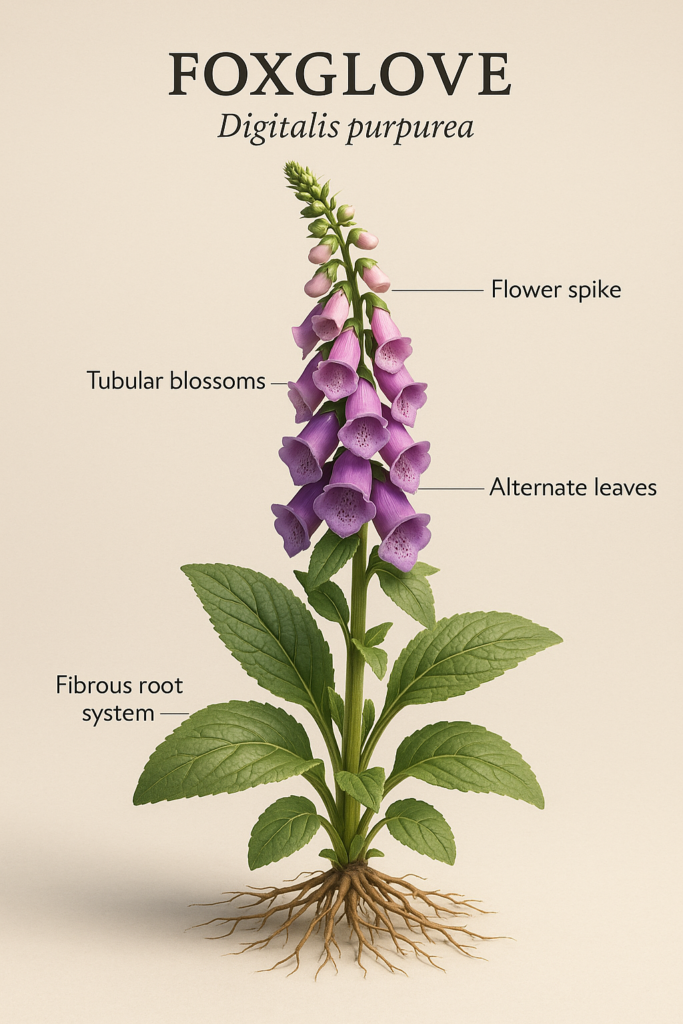

Foxglove is also a medicinal plant — Digitalis compounds extracted from it have pharmaceutical value. But farmers should never attempt handling extraction or processing. It is toxic without proper control. The safest earning route is flowers, not medicinal processing.

Every farmer considering Foxglove must ask one question Honestly:

“Does my climate allow cool-season discipline?”

If the answer is no, then the best decision is not to grow it. This honesty saves money.

FAQS

Why do most farmers fail with Foxglove?

Because they treat it like a regular annual, ignoring its need for cool nights and gradual cold exposure.

Why do spikes remain short?

High temperatures during early growth stop vertical bud formation.

Why do buyers reject Foxglove?

Bent stems, uneven spikes, or fully open bells make the flower unsuitable for professional use.

Can it grow in warm regions?

Only with controlled nurseries. Open-field warm climates usually fail.

Why does Foxglove rot at the base?

Evening overhead irrigation causes crown rot.

Should beginners grow Foxglove?

Not unless they have a reliable cool-season window or protected cultivation.

Why does flowering skip entirely?

Lack of winter-like conditions prevents vernalization.

Is Foxglove profitable?

Only when sold to premium florists or export buyers.

Do seeds or transplants perform better?

Seeds offer more control but require precise timing; transplants are safer for beginners.

What is the biggest mistake new growers make?

Focusing on leaf growth instead of climatic suitability and market planning.

Final Honest Conclusion

Foxglove rewards discipline, not enthusiasm.

It succeeds only when climate, timing, and market alignment are correct.

This article exists to prevent growers from walking blindly into a crop that looks easy but behaves like a specialist.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇