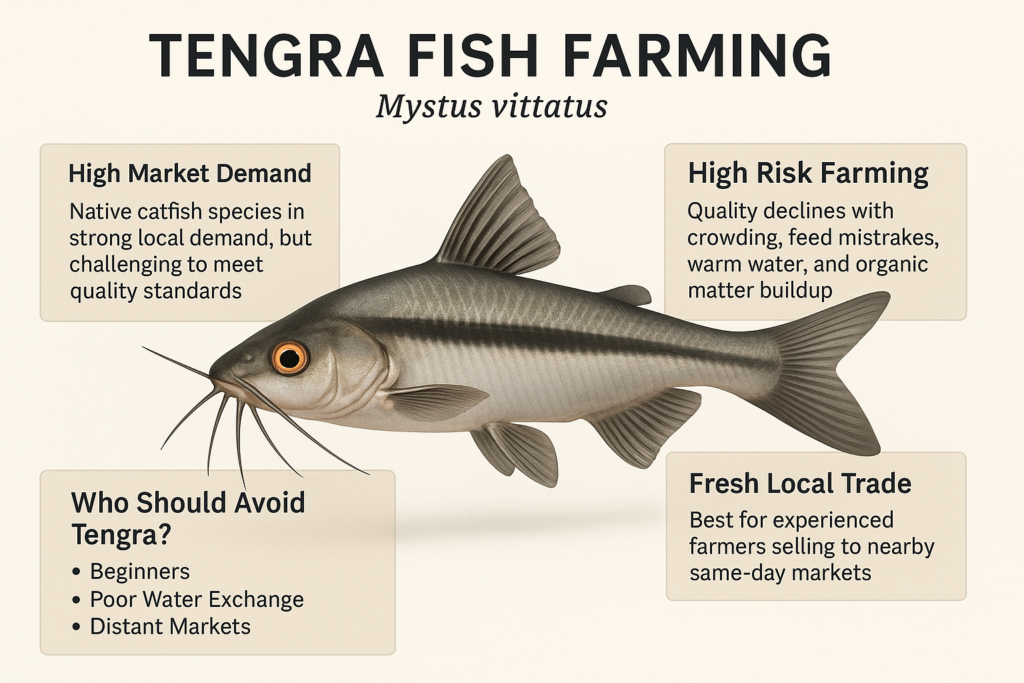

The first mistake most farmers make with Tengra is believing demand equals profit. Walk into almost any local fish market in eastern India or Bangladesh and you will see Tengra selling fast. The price board looks attractive. Traders shout rates that sound far better than carp or tilapia. This is exactly where the trap begins.

Tengra is not rejected because it doesn’t sell. It is rejected because quality collapses very easily, and the market does not forgive mistakes.

I have seen ponds full of Tengra where survival was high, feed cost was controlled, harvest volume looked good and yet the entire batch sold at throwaway prices. Not because the fish were dead or diseased, but because flesh texture, smell, and size uniformity failed buyer expectations. This is the first reality most YouTube videos never talk about.

Tengra buyers are not emotional buyers. They are extremely sensory buyers. They check firmness with fingers. They smell the gills. They break one fish to see flesh fibre. The moment flesh feels soft or watery, price collapses instantly. Farmers don’t understand this until the day they stand in the market helpless.

The second misconception is that Tengra behaves like other catfish. It does not. Tengra is far more sensitive to water stagnation and organic overload. In ponds where feed settles too much or where manure is used carelessly, Tengra grows fast but loses flesh strength. Yield looks good on paper, but market value dies.

Another silent killer is density illusion. Many farmers push stocking density after seeing high survival in the first month. Tengra tolerates crowding early, but quality degradation starts silently from the third month. Oxygen fluctuation, micro-stress, and internal fat imbalance do not kill the fish — they ruin the product.

Climate also plays a double game. Warm water accelerates growth but shortens shelf life. In peak summer harvests, Tengra fetched good morning prices but collapsed by afternoon because flesh softened faster than expected. Farmers blamed transport, but the real issue was metabolic stress accumulated weeks earlier.

Feed advice online is one of the biggest reasons farmers lose money. High-protein feed increases weight but destroys texture if timing is wrong. Tengra does not need aggressive protein throughout the cycle. Late-stage feeding errors are the main reason buyers reject batches even when size is correct.

Who actually makes money with Tengra?

Not beginners.

Not first-cycle farmers.

Not people copying carp or pangasius models.

Profitable Tengra farming usually comes from:

farmers already experienced with small indigenous fish

those supplying same-day local markets

ponds with excellent water exchange

farmers who harvest in small batches, not bulk

Export dreams with Tengra are mostly unrealistic. Processing units avoid it because flesh stability is unpredictable. This fish belongs to fresh, fast, local trade, not long supply chains.

There are also farmers who should never try Tengra. If water exchange is difficult, if feed control discipline is weak, if nearby market is more than a few hours away, this fish will punish mistakes brutally. In such cases, carp or even koi gives safer returns.

Tengra is not a bad fish. It is an unforgiving fish.

That is the difference.

FAQs (Real Decision Questions)

Is Tengra farming good for beginners?

No. It looks simple but punishes small mistakes.

Why do buyers reject even healthy-looking fish?

Because flesh softness and smell matter more than survival.

Is high density profitable?

Only in early stages. Long-term quality suffers badly.

Is this better than carp?

Only if you already understand market timing and quality control.

Who should avoid Tengra completely?

Farmers without fast local markets or water exchange capacity.

Final Judgment

Tengra farming is profitable only for farmers who respect market psychology more than pond yield. If your strength is discipline, timing, and quality control, Tengra rewards you. If you chase volume, shortcuts, or online formulas, this fish will quietly erase your profit without warning.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/mola-fish-amblypharyngodon-mola-farming-global-guide/