Cumin, globally known as one of the most valuable dry spices, holds a powerful cultural, culinary and economic importance. The spice comes from the dried seeds of Cuminum cyminum, a drought-tolerant aromatic plant that thrives in arid and semi-arid climates. Across India, Turkey, Syria, Egypt, Iran, China, Morocco and Mexico, cumin farming forms a vital part of rural agriculture, supporting farmers with strong export demand and premium market value.

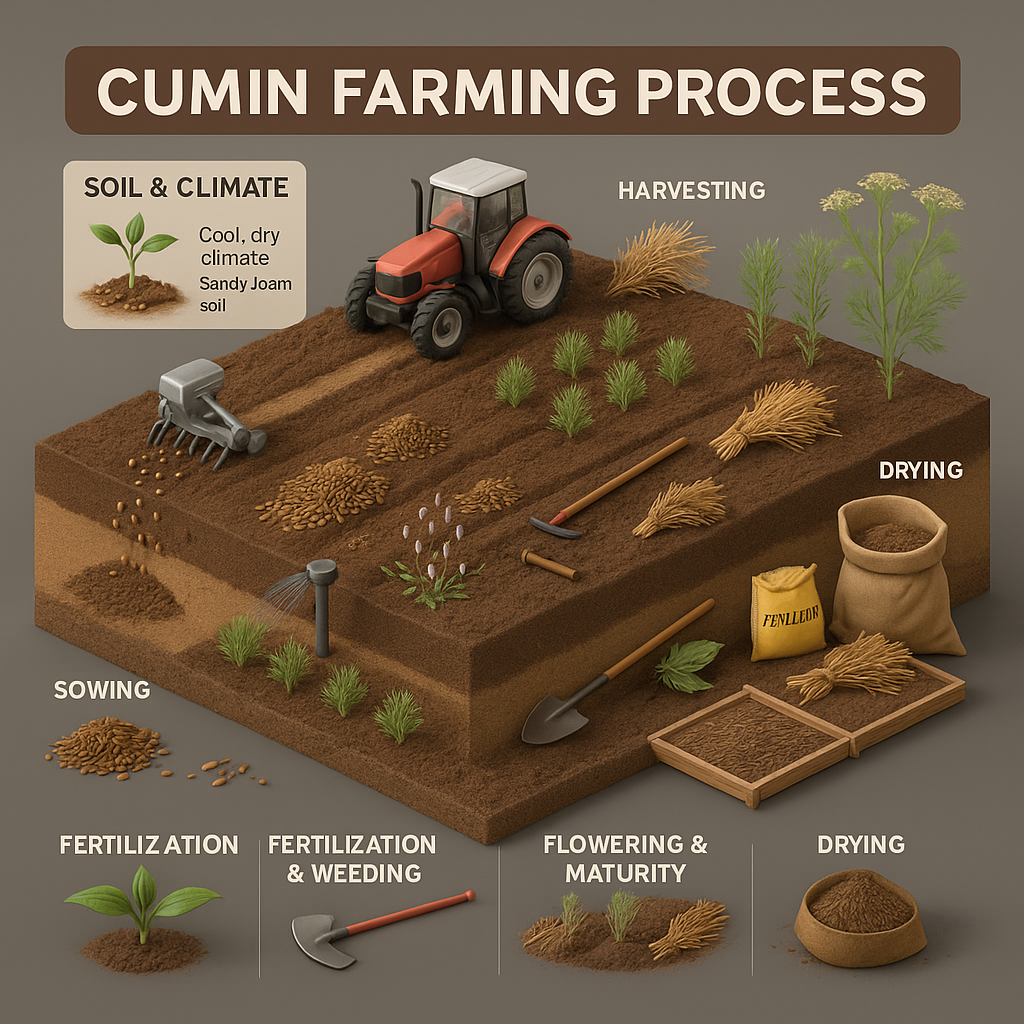

Cumin is a unique spice crop because it performs best where many other crops fail. Dry climates, sandy soils, low humidity and cold winters suit its physiology. The plant’s lifecycle, delicate flowering structure and sensitivity to moisture make it challenging but highly rewarding when managed correctly. Farmers across continents approach cumin farming as a precision-timed crop — sown under cool conditions, grown under dry air and harvested under clear skies.

The global spice market has witnessed immense demand for cumin due to its culinary significance. Cumin forms the backbone of spice blends worldwide — from Indian masalas to Middle-Eastern seasoning, Mexican foods, African stews and European herbal mixes. Its aromatic compounds such as cuminaldehyde provide its signature flavor and medicinal value. In recent years, cumin has gained traction in nutraceutical markets due to its digestive, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and metabolic regulation benefits. As global spice consumption grows, cumin prices often rise sharply, making it a high-value cash crop for farmers worldwide.

Climate defines cumin farming success. The crop requires cool weather for vegetative growth and warm, dry weather for seed development. Optimal temperature during germination ranges between fifteen and twenty degrees Celsius. During flowering and seed formation, temperatures between twenty and twenty-eight degrees support strong aromatic profile. Rainfall or humidity at flowering stages leads to fungal disease and flower drop. Therefore, the world’s major cumin zones are naturally dry regions with well-defined winter seasons.

Soil requirements for cumin emphasize drainage and light structure. Sandy loam, loam and light clay-loam soils are ideal. Heavy clay soils that hold moisture encourage fungal infections. Cumin roots penetrate shallow but require aerated soil free from compaction. Organic content strengthens microbial activity and improves seed filling. A soil pH between six and eight suits cumin. Salt-affected soils must be avoided because cumin is highly sensitive to salinity.

Land preparation begins with deep ploughing to break compact layers. The field must be leveled properly to prevent water stagnation. After ploughing, soil is harrowed to create a fine tilth suitable for small seeds. Cumin seeds require close contact with soil for uniform germination. Farmers incorporate compost or well-decomposed organic manure during land preparation. Excessive nitrogen must be avoided because it stimulates foliage at the cost of seed formation.

Seed selection plays a crucial role in cumin farming. High-yielding varieties adapted to region-specific climates provide stable performance. Seeds must be disease-free because cumin is vulnerable to seed-borne fungal infections. Before sowing, seeds are often treated with organic microbial protectants that prevent damping-off and early fungal issues. Seed rate varies by region but generally ranges between eight and fifteen kilograms per hectare depending on seed size and purity.

Sowing cumin is a precise agricultural activity. Farmers sow seeds during cool winter months, typically from November to early December in South Asian regions, while Mediterranean zones sow in late autumn. Timely sowing ensures that flowering occurs under dry, stable weather. Seeds are broadcast or line-sown at shallow depth. Line sowing provides better aeration, easier weed management and stronger plant structure. Germination begins within one to two weeks depending on soil moisture.

Irrigation in cumin farming requires careful control. Excess moisture at any stage increases disease pressure and reduces yield. Farmers apply irrigation immediately after sowing to ensure germination. The next irrigation occurs after twenty to twenty-five days depending on soil dryness. During flowering, irrigation is avoided because water exposure leads to flower shedding and fungal infection. A final light irrigation may be applied at early seed-setting stage in extremely dry climates. Over-irrigation severely damages cumin fields.

Nutrient management focuses on balanced nutrition. A moderate amount of organic manure supports microbial health. Excess nitrogen causes lodging and reduces seed quality. Potassium enhances seed development and boosts oil content. Micronutrients, particularly zinc and sulfur, improve aroma and plant vigor. Organic cumin production is increasingly popular due to export demand for chemical-free spices. Farmers use compost, neem cake and natural soil boosters to enrich land sustainably.

Weed control is essential in cumin farming. Because cumin plants grow slowly in early stages, weeds can easily dominate fields. A clean seedbed, timely manual weeding and shallow hoeing maintain field hygiene. Chemical herbicides are avoided in high-quality organic cumin production.

Pest and disease issues vary across climates. Aphids, thrips and mites commonly attack cumin foliage. Dry air helps reduce insect populations naturally. Fungal diseases, especially wilt, blight and powdery mildew, pose serious threats in humid conditions. Good air circulation, proper spacing and controlled irrigation reduce fungal incidence. Seeds must be treated before sowing to prevent early-stage diseases.

As cumin matures, the plant develops delicate umbels. Each umbel contains tiny flowers that transform into elongated seeds that are harvested for spice use. Flowering begins sixty to seventy days after sowing. Seed maturity occurs ninety to one hundred twenty days after sowing depending on climate. Dry weather during harvesting ensures high-quality seed. Farmers avoid harvesting during morning dew to prevent moisture contamination.

Harvesting cumin requires skill and timing. When seeds turn brown and detach easily, farmers cut plants manually and tie them in bundles. These bundles are dried under shade or mild sunlight. Excess sun exposure reduces essential oil concentration. Once dried, plants are threshed to remove seeds. Threshing is done manually or with mechanical threshers. Cleaned seeds undergo grading based on size, aroma and purity.

Processing cumin for market involves cleaning, winnowing, sorting and packaging. Export-quality cumin must meet strict standards for purity, aroma, moisture content and absence of microbial contamination. Seeds are often sterilized through natural processes such as controlled drying. Some manufacturers produce cumin powder, roasted cumin, cumin oil and oleoresins. Cumin oil is extracted through steam distillation and used in flavoring, perfumery and pharmaceutical applications.

Global markets for cumin remain strong. India dominates production and export. Other producing countries cater to regional markets. Cumin prices fluctuate based on weather, disease outbreaks and export demand. Premium-grade cumin fetches higher prices in international spice markets. The spice sells between two and eight USD per kilogram depending on grade, season and global stock levels. Cumin oil commands significantly higher value due to its concentrated aromatic compounds.

Economically, cumin farming offers strong profitability in dryland zones where few crops survive. Low water requirement, strong international demand and high value per kilogram make cumin a reliable cash crop. Farmers who manage moisture, disease and timing achieve excellent returns. Organic cumin, in particular, sells at premium rates in Europe, the United States and Middle Eastern markets.

Sustainability practices in cumin farming include crop rotation with pulses and cereals, organic soil building, minimal irrigation and biological pest management. The crop improves soil structure and reduces erosion in arid regions. Because cumin fits well into dryland ecological systems, it supports climate-resilient agriculture.

In conclusion, cumin farming stands as one of the most profitable and globally demanded spice enterprises. Its delicate nature requires precision, but when cultivated scientifically, cumin rewards farmers with premium yields and high international market value. This guide provides the complete insight needed to cultivate cumin successfully in both traditional and modern farming systems.

FAQ Cumin Farming

Farmers often ask how long cumin takes to mature, and the crop usually reaches harvest between ninety and one hundred twenty days depending on region and moisture conditions. Another common question concerns irrigation, and cumin needs minimal water with great caution during flowering. Soil suitability frequently arises, and sandy loam or loamy soil with strong drainage performs best. Many growers wonder why flowering drops, and sudden humidity or irrigation during flowering is the most common cause. Disease concerns often involve wilt and blight, which are minimized through seed treatment and proper airflow. Growers ask about organic cumin, and demand is strong in international markets with premium pricing. Seed rate questions arise often, and around eight to fifteen kilograms per hectare is standard depending on seed purity. Questions about harvesting time focus on seed color, and cumin is harvested when umbels turn brown. Market fluctuations remain a major concern, and cumin prices depend heavily on global supply and weather conditions. Finally, growers ask about yield improvement, and early weed control, balanced nutrition and perfect irrigation timing remain the most powerful factors.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love farming Love Farmers