The first impression you get when you walk into a bottle gourd field at sunrise is the strange softness of the air. Unlike brinjal or tomato plantations, the leaf canopy of bottle gourd behaves almost like a natural shelter. Large heart-shaped leaves spread across the trellis, catching the first golden rays of morning light. These leaves do not shimmer; they absorb lightnot brightly, but warmly. Beneath them, the vines move like slow creatures waking up from sleep. Bottle gourd is a climbing crop, but it does not grow with aggression. It grows with patience, extending its tendrils in careful, deliberate movements, as if choosing which direction would best suit its day.

Bottle gourd has a quiet dignity.

It doesn’t announce itself with strong odours or flashy flowers.

Its white blossoms open at dusk, releasing a sweet, faint fragrance noticeable only to those who pay attention.

The fruit itself grows silently, often surprising farmers who return after two or three days to find a tender green bottle where last week there was only a flower.

One acre of bottle gourd farming is not just a vegetable cultivation plan—it is a rhythm-based system. Everything in this crop responds to rhythm: irrigation rhythm, sunlight rhythm, temperature rhythm, even wind rhythm. Bottle gourd vines behave like living water—they stretch, curl, climb, and bend based on how the environment speaks to them.

The story begins with soil.

Bottle gourd roots explore widely and deeply.

They demand breathing space, but they also demand moisture.

The farmer who understands bottle gourd soil knows that the land should never feel sticky or hard. When you take a handful of perfect soil, it should hold shape lightly and break gently—like a firm cake crumb.

Climate shapes bottle gourd character more than any other factor. Warm climates bring faster fruiting; cooler climates bring stronger vines. But extreme heat exhausts the plant. Extreme cold stops it. The perfect climate lies between comfort and challenge—a zone where the plant feels nurtured but still alert.

Preparing the land is a slow, thoughtful process.

Farmers plough deeply not because bottle gourd roots demand it, but because loose soil encourages vines to stay healthier longer.

Organic matter compost, decomposed manure, microbial mixtures creates a biological cushion beneath the soil surface.

This cushion holds water like a sponge, releasing it slowly so the plant never feels thirsty suddenly.

Nursery raising is often unnecessary for bottle gourd. Many farmers sow directly, trusting seeds to emerge through the warm soil. But in regions with heavy pest pressure, nursery seedlings provide a safer start. A healthy seedling looks confident thick stem, broad cotyledons, upright posture. If a seedling appears uncertain at this stage, it rarely becomes a strong vine later.

Transplanting or sowing is followed by the most important decision:

direction of vine training.

Bottle gourd plants can grow along the ground, but fruits get scarred, plants suffer pest attack, and yield drops.

The trellis system transforms the crop completely.

When vines climb upward, they breathe better, flower better, and fruit better.

Farmers who invest time in building a strong trellis never regret it.

Once vines begin climbing, the field acquires a new personality.

Leaves create shade underneath, forming a microclimate 3–5°C cooler than outside.

This inner climate protects roots and fruits from harsh weather.

It is inside this shaded zone that the bottle gourds develop their signature tenderness.

But vines do not grow in straight lines. They wander.

A farmer guiding bottle gourd vines often feels like guiding children—gentle nudges, soft corrections, small encouragements.

This relationship between human and plant builds a field full of harmony.

Irrigation becomes a psychological language.

Bottle gourd hates emotional watering.

A flood after dryness causes yellowing, leaf curl, and fruit bitterness.

Steady moisture creates crisp, tender fruits with thin skin.

Farmers check soil with their fingers, not thermometers.

If the soil feels cool two inches deep, the plant is satisfied.

If the soil feels warm and dry, the plant is silently asking for water.

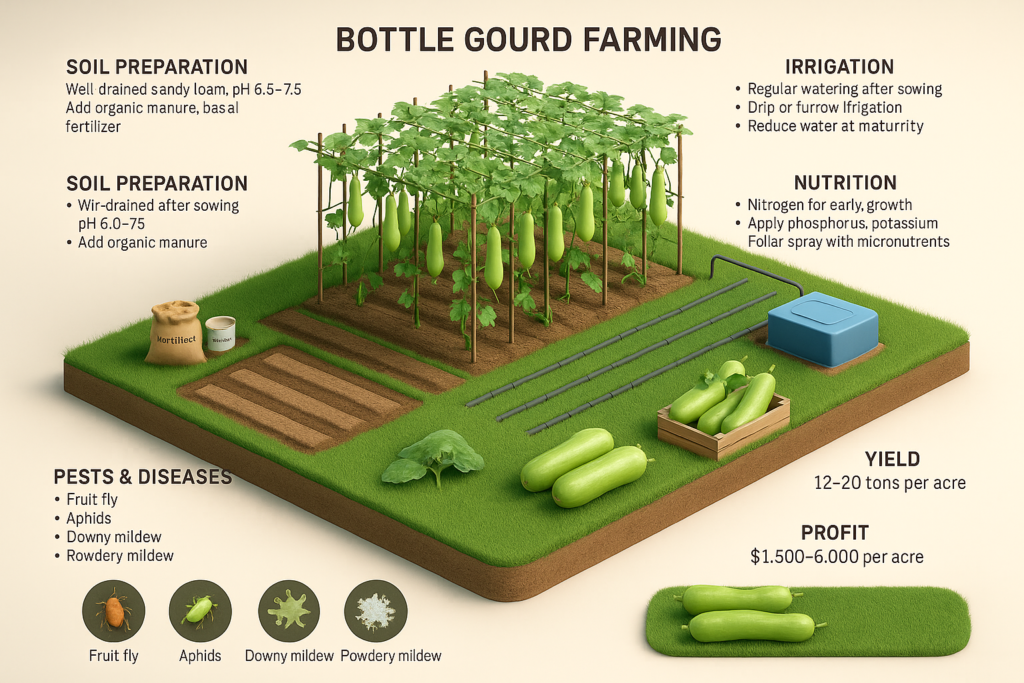

Nutrition follows growth stages.

Early growth demands nitrogen—just enough to expand leaves, not enough to make the plant overconfident.

Flowering demands potassium—to support fruit weight and outer shine.

Micronutrients decide leaf health—iron for greenness, boron for flower strength, calcium for fruit firmness.

Bottle gourd never hides its needs.

Leaves pale when nitrogen is low.

Margins burn when potassium is low.

Flowers drop when boron is deficient.

Farmers who watch carefully catch problems before they grow.

Flowering is one of the most elegant phenomena in a bottle gourd field.

White flowers open close to sunset, absorbing the last hour of light.

Moths and night insects help pollination.

Sometimes farmers hand-pollinate early morning to increase fruiting.

If the climate remains stable, every healthy flower has the potential to become a fruit.

Fruit development is astonishingly fast.

A tiny fruit that looks like a green thumb grows into a market-ready vegetable within days.

Farmers must harvest regularly—often every two days.

Regular harvesting stimulates the vine to produce more flowers, more fruits, more life.

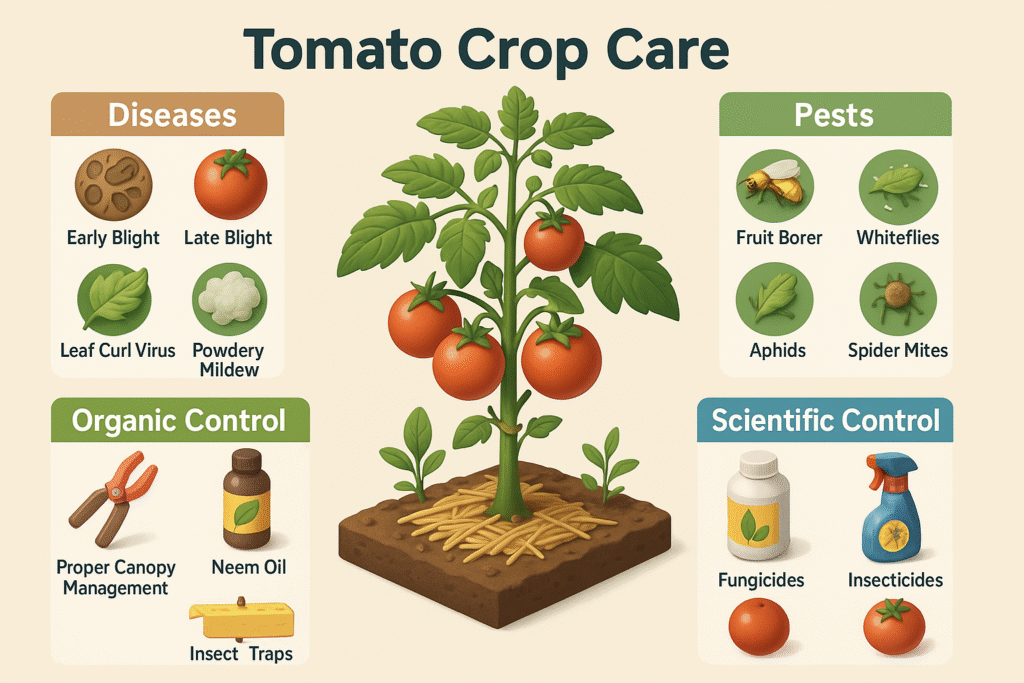

Pests appear as shadows rather than monsters.

Fruit fly lays eggs beneath the skin.

Aphids cling silently to tender shoots.

Leaf-eating caterpillars scrape foliage.

But a well-ventilated trellis reduces half the battle.

Bottle gourd plants grown on the ground suffer more pests because humidity traps around leaves.

Diseases follow moisture imbalance.

Downy mildew prefers humid evenings.

Powdery mildew arrives in dry heat.

Anthracnose spots leaves after rain.

But a good trellis and morning irrigation reduce disease almost magically.

Harvesting bottle gourd feels like uncovering promise after promise.

Each fruit feels cool in hand, smooth in texture, firm but gentle.

A good bottle gourd has a soft, fresh aroma—a sign of perfect hydration.

Farmers know readiness by the sound:

a tender gourd gives a dull, soft thump when tapped;

an over-mature one gives a hollow sound.

Yields differ widely across the world.

Small systems produce modest harvests.

Professional trellised systems produce astonishing yields.

One acre typically yields:

Low input: 8–10 tons

Medium input: 12–15 tons

High input: 16–20 tons

Commercial systems: 22–30 tons

Prices vary by region:

USA: $1–3/kg

Europe: $1.5–4/kg

Middle East: $0.8–2/kg

Asia: $0.2–1/kg

Profit per acre ranges from $1,500 to $6,000 depending on season and region.

But beyond economics, bottle gourd farming teaches emotional balance.

It teaches patience without frustration.

It teaches observation without panic.

It teaches that plants speak softly, and farmers must learn to listen.

A one-acre bottle gourd field is not just a vegetable project.

It is a daily conversation between nature and intention.

And the world will always need this humble, universal vegetable

which means the world will always need the hands that grow it.

✍️ Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/one-acre-turmeric-farming-global-complete-guide/