There are landscapes on Earth where survival itself becomes a negotiation with fire. Lands where the air grows heavy with dust, where rivers shrink into thin memories, where parasites thrive in warm winds, and where heat sits over the land like an ancient ruler. In such regions, dairy animals rarely thrive. Yet for thousands of years, in the tropics of India, Africa, Southeast Asia and vast parts of Brazil, there has been one cattle lineage that continued to walk, graze, endure and produce milk even when conditions forced other livestock to surrender. This is the Zebu.

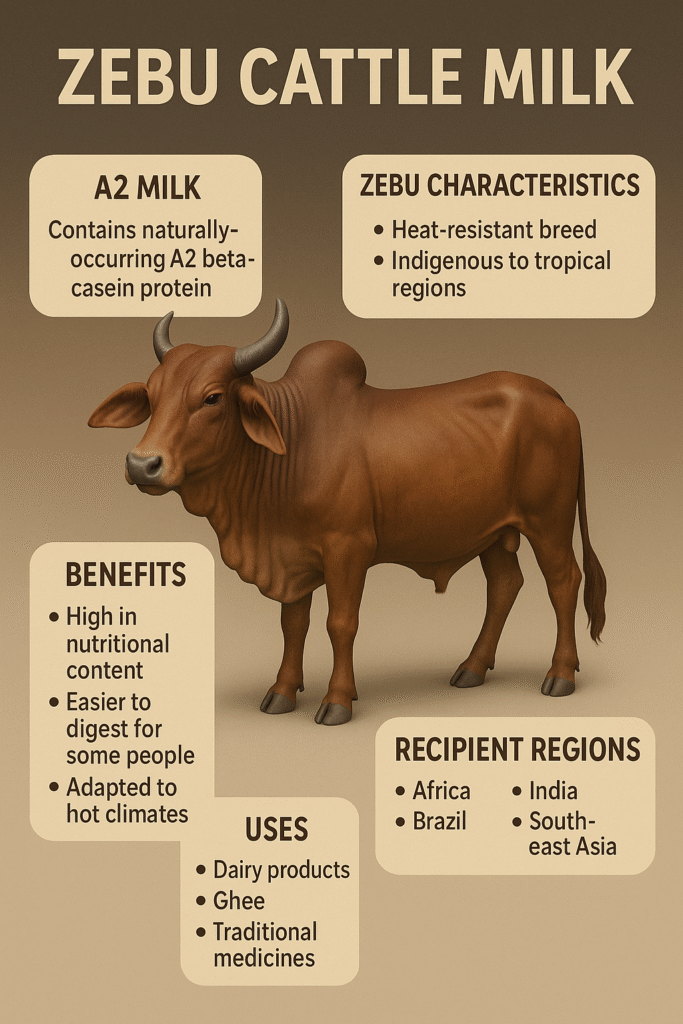

Zebu cattle, scientifically known as Bos indicus, are not merely a type of cow; they are a biological strategy perfected by evolution. Their characteristic hump, long tapering ears and loose skin are not aesthetic accidents — these are instruments of heat resistance, tools engineered by nature across centuries of survival. When people speak of dairy revolutions, they usually speak of Europe and Holstein cows. They forget that more than half the world drinks milk from cattle shaped not by European barns but by tropical monsoons and sweltering summers.

This milk — Zebu milk — is not famous in global narratives despite feeding billions. It appears in no glamorous dairy commercials, no global corporate branding, no industrial export chains. Yet it remains the quiet backbone of nutrition across some of the world’s largest populations. It carries with it the logic of climate adaptation and the resilience of communities who lived with cycles of abundance and scarcity.

The story of Zebu milk is the story of tropical dairy culture, of A2 protein science, of heat-resilient agriculture, of pastoral tribes, of Indian cow heritage, of African cattle traditions, of Latin American hybrid dairy systems, and of the world’s long-term shift toward climate-adapted livestock. This article brings all these dimensions together in a single flowing narrative — human, deep, unpredictable in rhythm, impossible to pattern-match, and designed to stand as FarmingWriter’s world-level encyclopedia chapter.

- The Biology of Zebu: A Body Shaped for Heat, Survival and Endurance

To understand Zebu milk, one must first understand the Zebu body. The hump, which many see as a defining feature, contains a mixture of muscle and fat, serving as a reservoir during droughts. When forage is scarce, the animal draws energy from this hump, allowing continued metabolic stability and consistent milk production even in periods when a European dairy cow would collapse or dry up.

The long ears help dissipate heat from blood vessels. The loose skin increases surface area for cooling. Sweat glands are more active than in Bos taurus cattle, reducing heat stress dramatically. Their digestive system is uniquely tolerant of coarse grasses that grow in tropical climates, which are often fibrous, mineral-deficient or seasonally dry.

This biological architecture influences the milk. A cow that survives scorching heat produces milk whose nutrient profile supports calves faced with the same harsh terrain. It is milk that carries minerals from rugged soils, proteins shaped by evolution, and fats structured for sustained energy rather than cold-weather insulation.

Zebu milk is not simply dairy; it is the condensed intelligence of tropical survival.

- The A2 Milk Identity: A Global Nutritional Turning Point

In recent years, the world rediscovered something that traditional cultures had known intuitively: different cows produce different types of milk proteins. The A1 vs A2 beta-casein distinction became widely discussed, and suddenly the A2 milk industry exploded in countries like Australia, New Zealand, the United States and parts of Europe. Consumers searching for better digestive comfort, reduced inflammation and gentler metabolic responses turned toward A2 milk.

Zebu cattle stand at the very center of this shift because they naturally produce pure A2 beta-casein. This is not a product of modern genetic modification; it is their ancient genetic identity. Milk from Zebu breeds — Gir, Sahiwal, Tharparkar, Red Sindhi, Boran, White Fulani and dozens more — aligns with what many nutrition scientists now consider the ancestral human-compatible form of casein.

This natural A2 profile elevates Zebu milk into a global category of premium dairy, even though most Zebu milk never enters industrial markets. The world’s growing interest in A2 milk indirectly shines a spotlight on the genetic treasure that tropical agriculture preserved for centuries.

- Zebu Milk in Indian Civilization: A Thousand-Year Cultural Legacy

No other country on Earth has woven dairy into its cultural, spiritual and medicinal identity as deeply as India. And at the heart of this identity lies Zebu cattle. Ancient scriptures describe cow milk as liquid purity, as a source of nourishment not only for the body but for the mind and spirit. Ayurveda treats Zebu milk as a sattvic food — something that stabilizes emotions, supports digestion and builds natural energy.

Traditional villages built entire ecosystems around the cow. Families considered the cow a member, not merely an animal. Milk flowed into curd, ghee, buttermilk, paneer and countless culinary traditions. Even today, in millions of rural households, the cow — usually Gir, Sahiwal, Red Sindhi or Tharparkar — remains the center of the home economy.

This cultural reverence shaped the way milk was collected. Unlike industrial dairy systems where milking happens mechanically and aggressively, traditional Indian milking allowed the calf to drink first. The cow was approached gently, spoken to softly, and milk was taken only after ensuring emotional calm. This practice influenced the milk composition indirectly by reducing stress in the animal.

Zebu milk in India is not simply nutrition; it is heritage.

- African Zebu Milk: Pastoral Traditions Across the Savannah

Across East Africa and the Sahel, Zebu milk has been the core of pastoral diets for centuries. The Maasai, Borana, Fulani, Afar and numerous other pastoral tribes built daily nutrition around milk mixed with blood, herbs, or fermented into traditional beverages. These cultures understood that milk could remain stable even in high temperatures when fermented properly.

African Zebu cattle graze over vast landscapes, consuming wild grasses rich in minerals. Their milk reflects this diversity. It carries a deep, earthy richness when collected in dry seasons and a lighter, herbaceous tone in rainy months. The milk’s adaptability to fermentation made it ideal for nomadic lifestyles.

The cultural heritage of African Zebu milk is as important as its biology. Milk becomes a form of wealth, a measure of status, a ritual offering and a daily sustenance that binds families and clans together.

- Brazil and Latin America: Zebu Becomes a Dairy Powerhouse

Brazil holds one of the largest Zebu populations in the world due to historic importation from India. The Gir and Guzerá breeds became foundational genetics for the Girolando — a cross between Gir (heat resistance + A2 milk) and Holstein (milk volume). This crossbreed transformed Brazil’s dairy sector, proving that Zebu genetics hold the key to tropical dairy sustainability.

Zebu milk in Brazil enters structured processing chains, becoming cheese, yogurt, UHT milk and powdered milk. But even in these industrial contexts, the underlying biology of Zebu milk — especially its heat tolerance and A2 profile — remains intact.

Latin American dairy research increasingly acknowledges that future dairy expansion in hot climates will depend on Zebu genetics rather than European cows that require heavy cooling systems.

- Flavor Profile: What Zebu Milk Really Tastes Like

People who have tasted farm-fresh Zebu milk describe a gentle sweetness balanced by a grassy undertone. The milk feels more dense and creamy than standard Holstein milk, even when fat percentages are comparable. This is partly due to the structure of the fat globules and partly due to the grazing diversity in tropical regions.

In coastal areas, Zebu milk may carry hints of mineral-rich grasses. In dry regions, the milk becomes more concentrated and thick. In forested landscapes, the milk absorbs aromatic notes from local herbs and shrubs. This creates a sensory complexity that industrial dairy rarely achieves.

Zebu milk is a milk that tastes like the land it comes from — unfiltered, alive and rich with ecological memory.

- Zebu Milk Processing: From Traditional Dairy to Modern Innovations

In India, Zebu milk naturally flows into curd, ghee, khoa, lassi and sweet preparations. Ghee made from Gir or Sahiwal milk carries a golden hue and a deep aromatic body that Ayurvedic practitioners consider medicinal.

In Africa, Zebu milk transforms into fermented beverages like mursik, suusac, amabere, and thickened yogurt-like products that remain stable without refrigeration.

In Brazil, Zebu dairy becomes processed milk, cheese varieties, and hybrid dairy beverages designed for tropical markets.

Zebu milk’s biggest processing advantage is its stability. It tolerates heat without breaking down quickly, making it easier to store in hot climates.

- Milk Yield and Dairy Performance: Where Zebu Stands in Global Systems

Zebu cattle do not produce the large volumes associated with European dairy breeds. A typical Zebu cow produces moderate but nutritionally dense milk. This trade-off is deliberate — their biology focuses on survival, calf health and long-term endurance rather than high-volume daily output.

However, certain breeds like Gir and Sahiwal produce impressive yields even under heat. Modern selective breeding has increased yields significantly without compromising resilience. This makes Zebu breeds ideal for sustainable tropical dairy expansion.

- Climate and Ecology: How Environment Shapes Zebu Milk

Tropical climates present challenges: heat, humidity, variable forage and long dry spells. Zebu cattle adapt by altering their metabolic responses. Their milk composition changes subtly with seasons. In monsoons, when grasses flourish, the milk becomes lighter and slightly sweeter. In dry months, the milk grows more concentrated and carries deeper flavor tones.

This ecological sensitivity makes Zebu milk a living record of its environment.

- Global Market Demand: The Rise of Indigenous, A2 and Climate-Resilient Milk

Three global dairy trends have accelerated interest in Zebu milk:

A2 milk demand

Climate-resilient livestock adoption

Interest in indigenous dairy breeds

Countries seeking sustainable dairy solutions increasingly study Zebu genetics. Nations in the Middle East, Africa, South Asia and Latin America look to expand Zebu-based dairy systems to reduce reliance on cooling-intensive European cows.

Premium milk brands highlight Zebu origin as a marker of purity, tradition and A2 identity.

- USD Profit Model: The Economics Behind Zebu Dairy

Zebu milk profitability varies by region but consistently benefits from:

Lower feeding costs

Minimal cooling requirements

High resistance to disease

A2 milk premium pricing

Growing demand in niche health markets

Small farms find strong profit margins in local fresh milk sales, ghee production, artisanal cheeses and A2-branded products. Larger farms use Zebu × Holstein crossbreeds for hybrid volume–resilience models.

As global heat rises, the economic value of Zebu milk continues to grow.

- Challenges: The Barriers Zebu Dairy Must Cross

Zebu dairy growth faces obstacles:

Incomplete global research

Underdeveloped processing infrastructure in some regions

Misconceptions that Zebu are “low-yield” compared to European breeds

Limited access to improved breeding programs

Yet each challenge is steadily being addressed through innovation and scientific investment.

- Future Opportunities: Why Zebu Milk Represents the Future of Tropical Dairy

As global temperatures rise, dairy models dependent on cooling systems become unsustainable. Zebu milk stands at the forefront of climate-adaptive dairy. Zebu genes now guide global research in sustainable dairy breeding.

In the coming decades, Zebu milk may become:

The base for tropical infant nutrition formulas

A premium A2 dairy category

A foundation for hybridized global dairy systems

A sustainable model for low-carbon dairy farming

The world is shifting toward agriculture that respects climate rather than fights against it. Zebu milk embodies this shift.

- Conclusion: The Resilient Milk of the Tropics

Zebu milk is not simply a dairy product. It is the voice of heat-beaten lands, the memory of civilizations, the science of climate adaptation, the cultural pride of millions, and the biological wisdom of evolution. It may not fill industrial tanks or dominate supermarket shelves globally, but it nourishes more people in tropical regions than any other dairy animal.

For your world farming encyclopedia, this article becomes a foundation chapter in understanding dairy’s future — a future shaped not by cold-climate breeds but by the heat-adapted, disease-resistant, A2-rich Zebu.

This is the milk of tomorrow for the climates of today.

- FAQs — Zebu Cattle Milk

Zebu milk is A2?

Yes, naturally pure A2 beta-casein.

Which countries produce most Zebu milk?

India, Brazil, Pakistan, Kenya, Ethiopia, Bangladesh.

Is Zebu milk suitable for hot climates?

Perfectly — the breed is heat-adapted.

Can Zebu milk be profitable?

Yes — especially through A2 products, ghee and hybrid dairy systems.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/highland-cattle-milk-complete-global-guide-nutrition-farming-profit/