Maca root has risen from the ancient highlands of Peru to international fame in a remarkably short period of time. Once a locally treasured Andean crop, today maca stands among the world’s fastest-growing superfoods. Its reputation as an energy booster, hormone-balancing tonic, endurance enhancer, fertility support root and overall vitality promoter has brought it into the center of global health industries. Smoothies, powders, capsules, sports nutrition blends, herbal supplements and natural health drinks all carry maca as a key ingredient. This rapid expansion has turned maca farming into a high-value agricultural opportunity that attracts farmers, exporters and wellness brands across continents.

Maca grows at altitudes rarely tolerated by conventional crops. Indigenous farmers cultivated it for over two thousand years on the cold, windswept plateaus of the Andes, often above four thousand meters. These harsh environments shaped maca into one of the toughest medicinal plants in agriculture. The roots developed extraordinary resilience, drawing minerals from volcanic soils and storing them in concentrated form. Modern research confirms maca’s exceptional nutritional and medicinal profile — rich in amino acids, minerals, alkaloids, glucosinolates and unique compounds known as macamides. These properties have elevated maca into one of the world’s most respected adaptogenic roots.

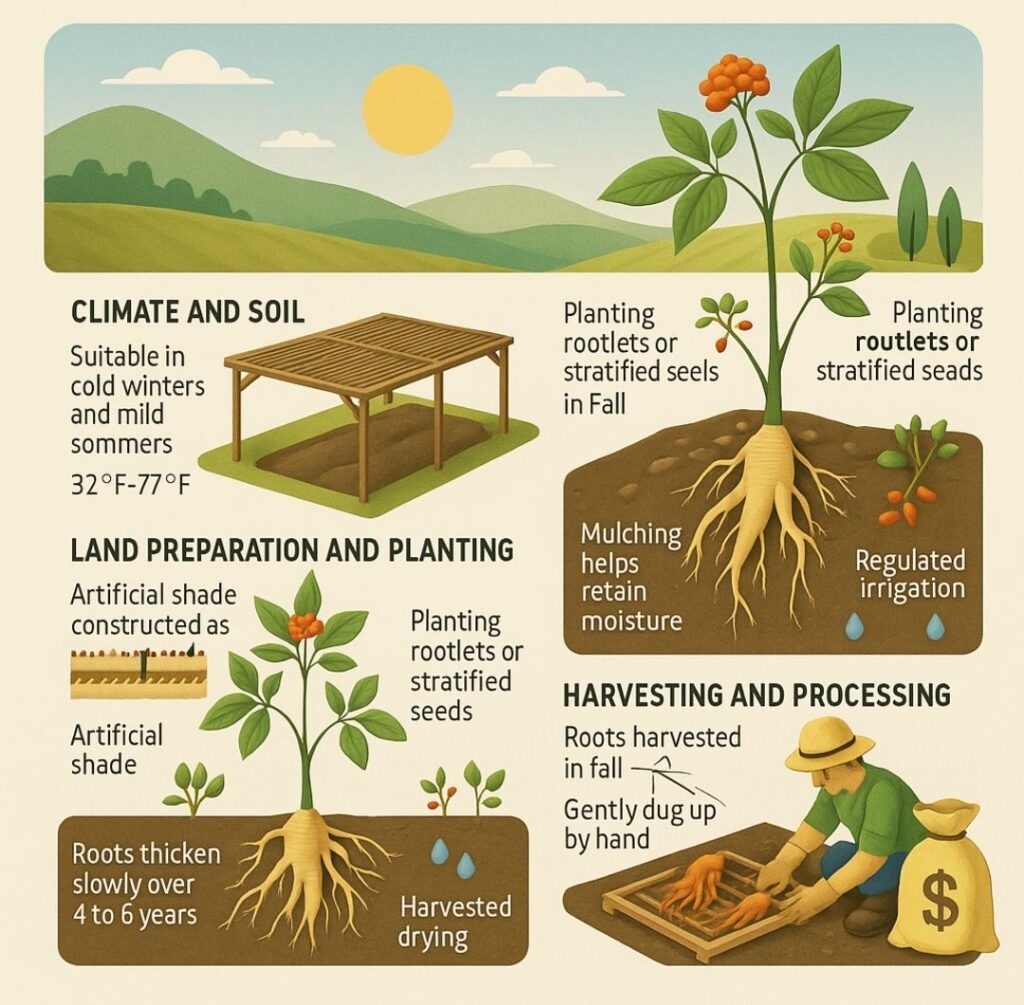

The natural climate of maca reflects a challenging combination of cold temperatures, strong UV radiation, low oxygen levels and intense winds. Maca thrives where temperatures drop below zero at night but rise moderately in the daytime. These thermal fluctuations stimulate root development, giving maca its dense, nutrient-rich structure. In traditional Peruvian regions, maca completes its growth cycle during the cool season with minimal rainfall. It prefers dry conditions, although moist soil during germination supports early establishment. Excessive heat or humidity, however, ruins the crop quickly, causing fungal infections and deformities in root shape.

Expanding maca cultivation globally requires understanding these ecological demands. Farmers outside the Andes replicate maca’s natural environment through high-altitude fields or cool-season farming in temperate regions. Highland areas of China, northern India, Nepal, Kenya and certain regions in North America and Europe have successfully grown maca. Climate remains the decisive factor — maca root forms properly only when exposed to cold nights and cool days. Growing it in warm lowland zones results in weak, watery roots unsuitable for commercial markets.

Soil characteristics play a vital role in maca physiology. The crop performs best in loose, well-drained, sandy loam soils enriched with minerals. Maca’s roots expand horizontally and vertically, demanding aeration and crumb structure. Heavy clay soil suffocates root growth, while overly sandy soil lacks nutrient retention. In the Andes, volcanic soil provides the perfect mineral-rich base. Farmers outside Peru artificially enrich soil with rock dust, compost, well-aged manure and micronutrient blends. A pH between five and seven supports healthy development. Excess nitrogen leads to leaf-heavy growth and stunted roots, so balanced nutrition is essential.

Land preparation follows a simple but precise approach. Deep tilling breaks hard layers, enhances aeration and ensures fine soil texture. Maca seeds are small and require shallow sowing. Before planting, the land must be free of stones, as root deformation reduces commercial value. Cool-season planting aligns with maca’s natural cycle. In temperate regions, seeds are sown in early spring or late autumn when temperatures remain low enough to mimic high-altitude climates.

Germination occurs within one to three weeks depending on temperature and moisture. Seedlings are delicate and require protection from excessive rain or rapid temperature changes. Once established, maca plants grow steadily but slowly, forming a leafy rosette close to the ground. The real growth happens underground, where the root gradually thickens. Over several months, the plant absorbs minerals and stores energy in the root bulb. Root shape varies depending on variety: some are round, others elongated, and the skin color ranges from yellow, red, purple, black to cream. Each color has distinct medicinal and commercial qualities, and global markets often demand mixed batches or specific premium colors.

Irrigation in maca farming must follow a disciplined strategy. The crop prefers moisture during germination but dislikes excessive watering afterward. Too much moisture invites fungal root diseases, especially in low-altitude areas. Drip irrigation or controlled sprinkling during early stages helps development. Once plants become established, irrigation frequency reduces significantly. The crop must experience cool, dry conditions as it moves toward maturity. Maca that grows in overly wet conditions loses its nutritional density and flavor profile.

Weed control remains essential during early growth because maca seedlings compete poorly with aggressive weeds. Farmers rely on manual weeding or shallow cultivation techniques to protect the shallow root zones. Chemical herbicides are avoided because maca is a medicinal crop, and global buyers demand pure, contamination-free powder. Many farmers use organic mulches early on, although excessive mulching is avoided in humid climates because it increases fungal pressure.

Pests and diseases in maca farming vary depending on region. In the Andes, the main threats include root borers and mild fungal infections, but outside Peru, maca faces new pathogens due to unfamiliar environments. Farmers must observe the crop carefully for damping-off, powdery mildew and root lesions. Organic fungicidal sprays, crop rotation and correct irrigation frequency keep disease risks minimal. Maca’s natural resilience often protects it from major outbreaks when grown in proper climatic zones.

As the crop approaches maturity, the leaves begin changing color and reducing growth. The roots swell beneath the soil, completing their formation of dense, nutrient-rich structure. Harvest occurs between six and nine months after planting depending on climate. In the Andes, maca is traditionally harvested after seven to eight months. Workers gently loosen soil and lift roots manually to avoid damage. Harvested roots are cleaned carefully without excessive washing to prevent moisture accumulation.

Processing begins with drying, one of the most critical phases in maca production. Traditional farmers dry roots under the sun for several weeks at high altitude, allowing natural oxidation and biochemical changes that enhance medicinal qualities. Modern drying systems use controlled dehydration, maintaining low heat to preserve nutrients. Once fully dried, maca roots become hard, lightweight and long-lasting. They may be stored whole or ground into powder. Global buyers prefer powder for ease of packaging and blending in supplements. Some industries use gelatinized maca, a heated and processed form that improves digestibility.

The global market for maca continues to expand rapidly. Demand comes from the United States, Europe, China, Japan, South Korea, India and South America. Health-conscious consumers use maca for hormonal balance, libido support, energy enhancement, mental clarity, stress reduction and athletic performance. Red and black maca varieties fetch higher prices due to their elevated medicinal properties. Export-quality maca powder often sells between twelve and thirty-five USD per kilogram depending on origin and quality grade. Premium raw roots can sell even higher.

Economically, maca farming provides strong profitability when climate conditions are correct. The crop requires low fertilizer inputs, minimal water after establishment and moderate labor compared to other high-value medicinal roots like ginseng. Margins remain strong because global supply is limited, and genuine maca commands premium rates. Farmers entering maca cultivation must consider long-term climate suitability because the crop’s quality depends entirely on environmental alignment. But when properly managed, maca root offers excellent returns with rising international demand each year.

Sustainability in maca farming involves protecting soil health, preserving high-altitude ecosystems, using organic nutrition and avoiding harmful chemicals. The crop fits naturally within eco-friendly farming models and responds well to organic methods. Maca also adapts well to agroforestry designs in cooler highland zones, promoting biodiversity and soil resilience.

In conclusion, maca farming stands as a powerful opportunity in global medicinal agriculture. Its combination of ancient heritage, modern scientific validation and consistent market demand transforms it into a premium crop for the future. Farmers who replicate maca’s natural ecological environment and maintain clean, organic cultivation practices can unlock exceptional commercial and medicinal value. This world-level human-written guide equips growers and global investors with a complete understanding of maca cultivation from seed to export.

FAQ

Farmers often ask how long maca takes to mature, and under ideal cool conditions, the crop typically requires six to nine months for complete root development. Another common question involves climate suitability. Maca grows best in cold high-altitude regions or temperate zones that mimic Andean weather cycles. Soil concerns also appear frequently because maca roots demand loose, mineral-rich, well-drained soil. Irrigation questions revolve around the crop’s sensitivity to excess water — maca needs light moisture early and dry conditions later. Growers also ask about profitability, and maca remains one of the most commercially attractive medicinal crops due to strong global demand. Disease concerns are usually related to humidity, but with proper drainage and rotation, most problems remain manageable.

✍️Farming writers Team

Love farming Love farmers