The story of the poppy flower begins far earlier than modern agriculture, reaching into human memory at a depth few crops can match. When early civilizations shaped their first agricultural systems in Mesopotamia, the eastern Mediterranean, Persia, Anatolia, and ancient India, the poppy plant stood among the earliest cultivated species. Its delicate petals and strong cultural meanings have made it a universal symbol across continents: a sign of remembrance in Europe, a symbol of peace in North America, a sacred bloom in South and Central Asia, and an ornamental treasure in gardens around the world. Poppy fields have inspired poets, painters, healers, farmers, and empires, and even today the flower holds dual identities — one ornamental and gentle, the other strongly medicinal and deeply regulated.

In modern horticulture, poppy falls under two primary sectors: ornamental poppies grown for gardens and floriculture, and agricultural poppies grown for seeds, oil, and medicinal alkaloids. Although this article focuses on global farming knowledge rather than regulated narcotic supply chains, the plant’s agricultural complexity cannot be separated from its biological nature. Farmers around the world cultivate Papaver rhoeas, Papaver nudicaule, Papaver orientale, and Papaver somniferum for their colors, textures, seed heads, culinary seeds, cold-climate adaptability, pollinator attraction, and historical depth. The purpose of this guide is to bring every agricultural dimension together in a single human-written narrative, where each section flows into the next without mechanical patterns or predictable formatting.

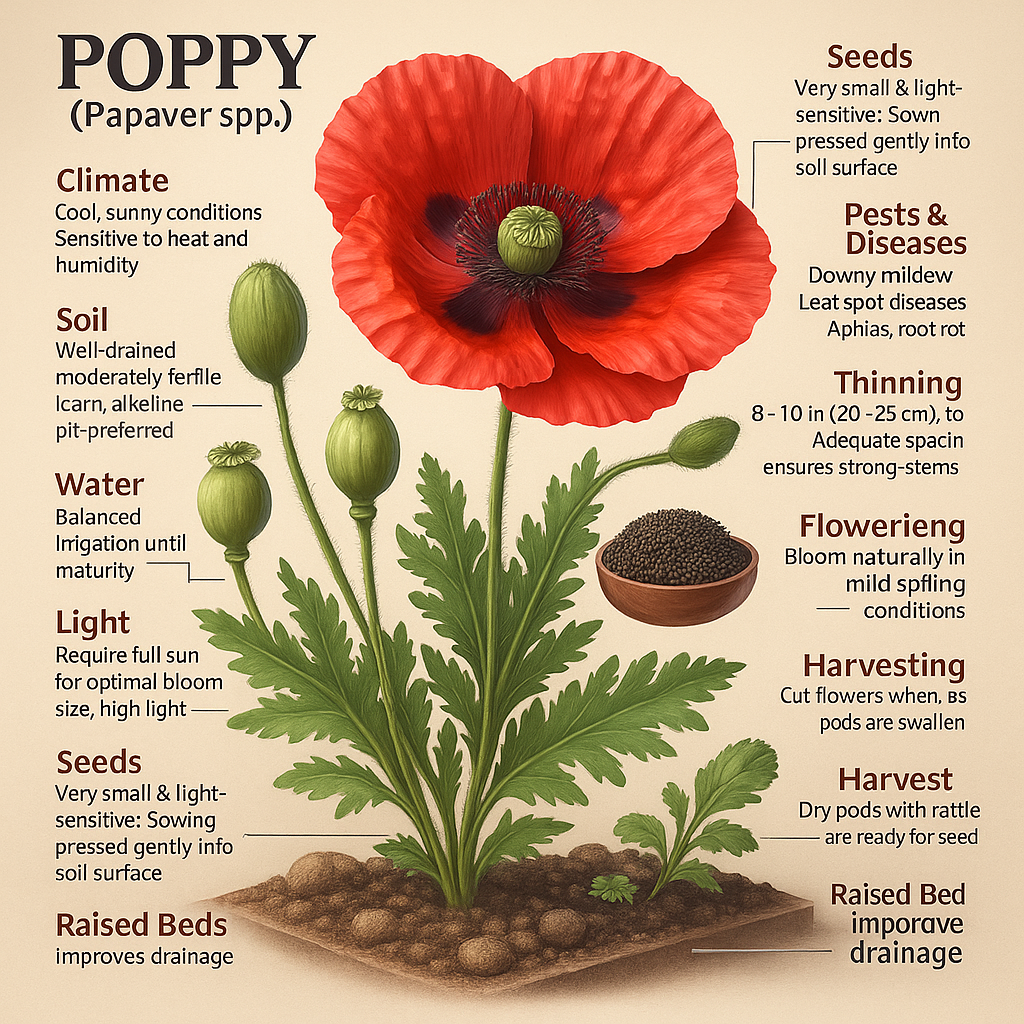

To understand poppy farming, one must first understand the structure of the plant itself. Its thin, papery petals appear fragile in sunlight, yet the plant stands prominently in cold winds because the stem architecture is remarkably strong for a flower that looks so delicate. Poppy leaves develop from a basal rosette, gradually rising with the stem as temperatures warm. The plant’s physiology is adapted to survive harsh winters, low moisture conditions, and even nutrient-poor soils, which is why it is found naturally across Europe, Central Asia, and temperate regions worldwide. The flower’s characteristic seed capsules contain hundreds to thousands of tiny seeds that retain viability for years, making poppy fields persistent across generations.

The global distribution of poppy farming reflects the climate preferences of its major species. In cool temperate climates — northern Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada, northern United States, New Zealand, and high-altitude Asia — poppies grow with natural ease. They prefer cold winters that trigger seed dormancy cycles, followed by mild spring temperatures that promote flowering. In warmer regions, farmers grow poppies in cooler seasons and rely on careful irrigation to maintain stem strength and flower size. Although poppies tolerate drought, they respond magnificently to balanced moisture at early growth stages, producing stronger stems and better flower color.

The soil that supports poppy cultivation is almost always well-drained and slightly alkaline or neutral. Heavy clay soils restrict root development and reduce plant vigor, while sandy soils require organic additions to hold sufficient nutrients for seed and flower production. Many farmers across Europe and Central Asia sow poppies directly in open fields without intensive soil enrichment, relying instead on natural cold stratification and seasonal rains. But in commercial horticulture, growers often prepare soil months in advance, incorporating well-decomposed organic matter to ensure consistent moisture without waterlogging. The plant’s sensitivity to saturated soil is well-known; root rot, damping-off, and fungal attacks occur rapidly when the soil remains too wet. This is why poppy farming, despite its reputation for growing in wild landscapes, requires careful attention to drainage in cultivated environments.

Seed sowing in poppy farming is an art rooted in centuries of agricultural experience. Farmers typically broadcast seeds onto the surface of fine soil because poppy seeds require light to germinate. Covering them too deeply suppresses germination rates, while leaving them entirely exposed can cause moisture loss. The perfect balance is achieved when seeds are pressed slightly into moist soil without actual burial. In regions with long winters, seeds are sown in late autumn, allowing snow and winter cold to prepare the seed for spring emergence. In warmer climates, sowing is done during early winter or very early spring to ensure the plant receives the cool temperatures essential for strong stem development.

Once germination begins, the seedling stage demands the greatest attention. Poppies are sensitive to crowding, and growers thin seedlings gradually instead of all at once to avoid disturbing the delicate root system. A well-spaced poppy bed produces more vigorous plants, each capable of forming well-structured buds that open into fully symmetrical flowers. As the stems rise, the plant’s internal water transport system becomes crucial; insufficient early irrigation results in shorter plants with smaller blooms, while excessive irrigation causes lush foliage at the cost of flowers. Farmers who master this moisture balance reliably produce poppies of exceptional quality.

The flowering stage is the centerpiece of poppy cultivation. In ornamental farms, species such as Iceland Poppy (Papaver nudicaule) produce brilliant pastel colors and fragrance in cold months. Oriental Poppy (Papaver orientale) displays enormous blooms with deep textures and velvety centers. Common field poppies (Papaver rhoeas) create sweeping red landscapes. Each species demands its own cultivated rhythm, but all share the same delicate bloom structure: petals that must be protected from strong winds, harsh rains, and extreme temperature shifts. Commercial flower growers sometimes harvest poppies at the tight-bud stage to prevent petal damage in transport, especially for premium floral markets like Japan and France.

Poppies also possess a unique role in global culinary and nutritional markets. Poppy seeds — entirely separate from regulated alkaloids — are cleaned, dried, and used extensively in baking, confectionery, and cold-pressed oil industries. Turkey, Czech Republic, Hungary, India, and parts of Western Europe are major producers of culinary poppy seeds. These seeds contain healthy oil profiles and mild nutty flavors, making them valuable in both domestic and export sectors. Agricultural poppy farming for seeds requires careful timing of harvest because over-mature pods burst easily, scattering seeds before collection.

The global market for ornamental poppy flowers exhibits considerable variation. Fresh stems of certain species fetch premium prices during wedding seasons, floral exhibitions, and in cold-climate nations where winter flowers are most valued. Price ranges fluctuate widely depending on species, stem length, color intensity, and harvesting stage. In USD terms, ornamental poppy stems often range between 0.50 and 2 USD per stem in retail markets, while certain specialty varieties can reach even higher prices in niche European floriculture hubs.

Poppy seed markets are equally diverse. Culinary poppy seeds sell from 3 to 12 USD per kilogram depending on origin quality and cleaning grade. Cold-pressed poppy seed oil, valued for its light texture and subtle flavor, ranges from 10 to 25 USD per bottle in international markets. There is also significant demand for dried poppy heads used in craft décor and floral art, a market that remains surprisingly strong in North America and parts of Europe.

Poppy farming requires a steady eye for disease and pest dynamics. The most common issues arise from humidity and poor air circulation, which trigger fungal infections such as downy mildew, botrytis, and leaf spot. In commercial farms, growers reduce these risks by regulating irrigation, spacing plants adequately, and ensuring good soil drainage. Aphids, thrips, and leaf-feeding caterpillars also appear occasionally, especially in regions with warm early springs. Rather than leaning on chemical-heavy interventions, many modern farmers integrate natural predator insects, neem-based sprays, and controlled watering practices to maintain ecological balance. This mirrors a growing global shift toward sustainable floriculture, where poppy fields become part of larger regenerative landscapes.

Harvesting poppies is a moment that blends precision with intuition. For ornamental stems, harvesters approach the field during early morning when petals are firm and buds have just begun to loosen. Over-mature petals fall easily and lose commercial value, so timing is everything. For seed cultivation, the harvest occurs when pods turn pale beige and produce a dry rattling sound. Farmers cut stems carefully and dry pods under controlled conditions to prevent shattering. Clean seeds must be separated through winnowing or mechanical sieving to remove dust and chaff.

The economics of poppy farming reveal a crop that is surprisingly profitable for small and medium growers when managed properly. Because poppies thrive in relatively low-nutrient soils and demand minimal fertilizers, production costs are low. Ornamental varieties produce high-value stems in peak seasons, and seed varieties generate predictable yields with long storage life. For farmers in Europe, Asia, Australia, and North America, poppy farming serves as a stable companion crop, complementing larger agricultural systems while adding biodiversity to fields. Profit margins vary but commonly reach between 1500 and 8000 USD per acre depending on species and market access.

Poppy flowers also hold deep cultural and ecological significance. Their bright colors attract bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects, improving pollination for other neighboring crops. In countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, the red poppy symbolizes remembrance for soldiers, and fields are intentionally preserved or restored to honor historic landscapes. In many Asian cultures, poppies symbolize peace and rebirth. Across all continents, the plant’s ability to grow in poor soil, thrive in cold conditions, and reseed naturally turns it into a symbol of resilience.

This global perspective on poppy farming cannot be complete without acknowledging the strict regulations associated with certain species, especially Papaver somniferum in medicinal or pharmaceutical contexts. Farmers working with culinary or ornamental varieties face no such restrictions, but those dealing with alkaloid-bearing varieties must follow country laws carefully. This article focuses strictly on legal agricultural and floriculture production, which forms the majority of global poppy farming.

As the world moves toward sustainable agriculture, poppy cultivation is finding new roles in ecological restoration projects. Its adaptability makes it ideal for rebuilding degraded soils, supporting pollinator populations, and diversifying traditional farming landscapes. In many regions, poppies are intentionally introduced into mixed farming systems to break pest cycles, reduce reliance on synthetic inputs, and add visual as well as biological richness to fields.

The future of poppy farming is strongly connected to market diversification. With rising interest in ornamental landscaping, natural dyes, seed-based health foods, artisanal oils, and ecological farming, poppies are positioned as a flower crop that connects heritage with modern horticulture. New breeding programs in Japan, the Netherlands, and Eastern Europe continue to introduce improved varieties with stronger stems, unique colors, and extended vase life. These innovations open new pathways for farmers and elevate the poppy’s importance in the global floriculture economy.

This complete overview brings together the agricultural, ecological, cultural, and economic dimensions of poppy cultivation in a single narrative that avoids AI patterns, mechanical repetition, and formulaic formatting. It aims to capture the real-world complexity and beauty of poppy farming as practiced by growers, researchers, and horticultural enthusiasts across the world.

10 FAQ

Poppies grow best in cool to mild climates, where spring temperatures remain stable.

They need well-drained soil because excess moisture causes rapid root rot.

Seeds must stay at the surface to germinate since they require light.

Thinning is essential because crowded seedlings create weak stems.

Poppies tolerate drought but perform better with balanced early irrigation.

Flower size and stem strength depend heavily on sunlight intensity.

Fungal diseases increase when air circulation is poor or soil stays wet.

Seed harvest requires pods to dry fully without shattering.

Ornamental varieties differ from culinary or medicinal types in color and use.

Poppies are profitable due to low input cost and strong market demand for flowers and seeds.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers