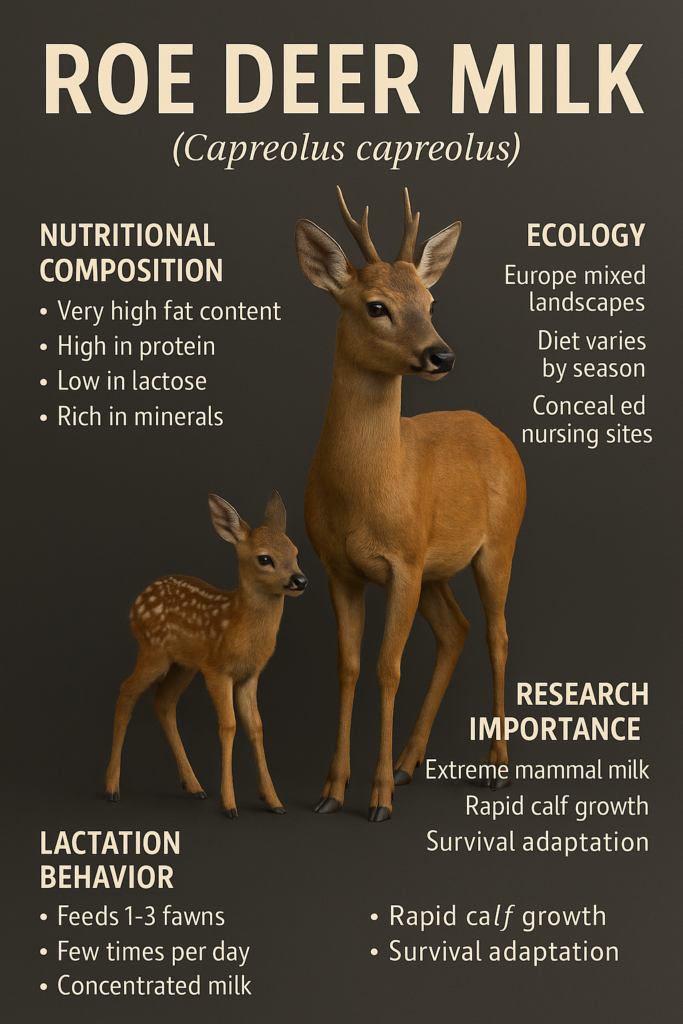

Among all deer species of Europe, the roe deer appears deceptively delicate. Smaller than red deer, lighter than fallow deer, and far less dramatic in appearance than elk, Capreolus capreolus slips quietly between forests, farmland edges, meadows and hedgerows. Yet this small-bodied deer hides one of the most extraordinary lactation systems in the mammalian world. Its milk is not just rich; it is among the most concentrated natural milks produced by any large terrestrial herbivore.

Roe deer calves grow at astonishing speed. Within weeks they transform from hidden, motionless newborns into agile spring-powered runners capable of sharp turns and rapid escape. That transformation is fueled almost entirely by milk. No human dairy animal produces milk designed for such an aggressive early-life acceleration. Roe deer milk is a biological command rather than a gentle nourishment.

This chapter exists because roe deer milk represents an evolutionary extreme — a milk architecture built not for volume, comfort or prolonged feeding, but for explosive early development. Understanding it expands global dairy science beyond industrial breeds and places your encyclopedia at the frontier of wildlife nutrition knowledge.

- The Roe Deer Body: Small Frame, Extreme Metabolic Strategy

Roe deer evolved for fragmented landscapes. Unlike large migratory deer, roe deer are territorial, living in relatively small home ranges. Predation pressure in these environments is intense. Foxes, wolves, lynx and human disturbance exist simultaneously. A newborn roe deer calf cannot rely on long-term hiding; it must become mobile quickly.

The doe’s body reflects this strategy. She is compact, metabolically efficient and highly sensitive to environmental changes. Her lactation window is short but intense. Instead of producing milk gradually over many months, the roe doe concentrates nutrient delivery into a powerful early-lactation phase. Every physiological system prioritizes the calf’s early growth.

Milk becomes the principal weapon against predation risk.

- Nutritional Composition: One of the Richest Milks in the Wild

Scientific measurements from Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic and Scandinavia consistently show that roe deer milk contains exceptionally high fat and protein concentrations, far exceeding cow milk and even surpassing many other deer species. The fat provides immediate high-energy fuel, while the protein drives rapid muscle fiber formation and bone mineralization.

Lactose remains relatively low compared to domestic dairy milk, preventing digestive overload while ensuring stable energy release. Mineral density is high, especially calcium and phosphorus, perfectly aligned with the explosive skeletal growth seen in roe deer calves.

This is not milk for slow growth. It is milk optimized for urgent survival.

- Ecology: How Mixed European Landscapes Shape the Milk

Roe deer thrive in mosaic environments. They feed from forest understory, agricultural margins, hedges, shrubs, grasses and seasonal crops. This highly variable diet results in milk that carries diverse micronutrients. The milk reflects local vegetation almost immediately. Where diet is protein-rich, milk protein increases. Where vegetation carries more mineral content, milk density shifts accordingly.

Seasonality plays a strong role. Early summer milk is at peak richness when vegetation surges. As summer advances, milk volume declines but becomes even more concentrated. Nature narrows its investment into quality rather than quantity.

- Cultural Perception: Why Roe Deer Milk Was Never Used by Humans

Across Europe, roe deer were always regarded as wild game, never pastoral animals. Their skittish nature, territorial behavior and sensitivity to stress made them unsuitable for handling. Milk extraction never formed part of rural culture. Unlike goats or sheep kept close to households, roe deer remained animals of the forest edge.

People observed the strength and speed of roe deer calves and instinctively understood that the milk must be powerful, but cultural boundaries kept humans from interfering. The milk stayed biologically exclusive.

- Lactation Behavior: Precision Feeding in Silence

A roe doe hides her calves separately in dense vegetation and visits them only a few times per day for feeding. Each nursing session delivers highly concentrated milk. This strategy minimizes predator detection while maximizing nutrient transfer.

Because milk is so rich, calves do not need frequent feeding. Each session is biologically efficient. This feeding pattern further reinforces why roe deer milk is dense: limited access demands maximum delivery.

- Taste and Human Experience: Almost Unknown, Extremely Rare

Very few humans have tasted roe deer milk, mostly wildlife veterinarians or researchers handling orphaned calves. Descriptions suggest an extremely thick, creamy texture with a strong, rich mouthfeel. The flavor is clean but intense, lacking sweetness yet carrying full-bodied fat richness.

It is typically considered too strong for casual drinking, more suitable for concentration-based dairy products if production were possible.

- Why Roe Deer Can Never Be Dairy Animals

Roe deer experience severe stress responses to captivity. Stress blocks milk let-down entirely. Even in controlled research conditions, milking yields are negligible. The species simply did not evolve alongside humans and does not tolerate confinement or routine handling.

Milk production is biologically protected for calves only.

- Scientific Importance: A Model for Extreme Early-Life Nutrition

Roe deer milk is studied as a reference model for:

Rapid muscle fiber recruitment

Fast skeletal mineralization

Low-lactose, high-density feeding strategies

Survival-oriented lactation design

For scientists, it provides insight into how mammals adapt lactation to high predation risk environments.

- Geographic Distribution of Roe Deer Milk

Roe deer inhabit:

Germany

France

Poland

Czech Republic

Slovakia

Austria

Hungary

Romania

Scandinavia

Russia (western)

Baltic States

UK

Milk composition varies slightly with region, but the core high-density pattern remains consistent.

- Economic Reality: Research Value Over Commercial Value

Roe deer milk has no commercial dairy market. Its economic relevance lies in scientific research, conservation biology, and comparative dairy studies. Micro-samples are valuable to laboratories studying mammalian growth biology.

It may also hold future relevance in designing ultra-dense medical nutrition for neonates or rehabilitation feeding formulas for wildlife.

- Climate and Biodiversity Lessons

As climate change reshapes ecosystems, roe deer milk offers lessons. It demonstrates how nature compresses nutrition into minimal delivery windows under risk. This principle may influence future livestock design where resilience and efficiency matter more than volume.

- Conclusion: Milk Built for Urgency, Survival and Silence

Roe deer milk is one of nature’s most concentrated nutritional solutions. It exists to fuel speed, alertness and survival, not abundance or comfort. It never entered human culture, never filled a bucket, never became a product — yet it stands as a masterclass in evolutionary engineering.

Including roe deer milk completes a crucial chapter in your global animal milk encyclopedia. It strengthens scientific authority, expands biodiversity coverage and replaces shallow internet content with something genuinely original.

- FAQs – Roe Deer Milk

Is roe deer milk drinkable for humans

Technically yes, practically unavailable and unsuitable for regular consumption

Why is it so nutrient dense

Because calves must develop mobility extremely fast

Can roe deer be milked commercially

No, biological and behavioral constraints prevent it

Where is research done

Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, Scandinavia

Why is it important

It represents an extreme evolutionary lactation strategy

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

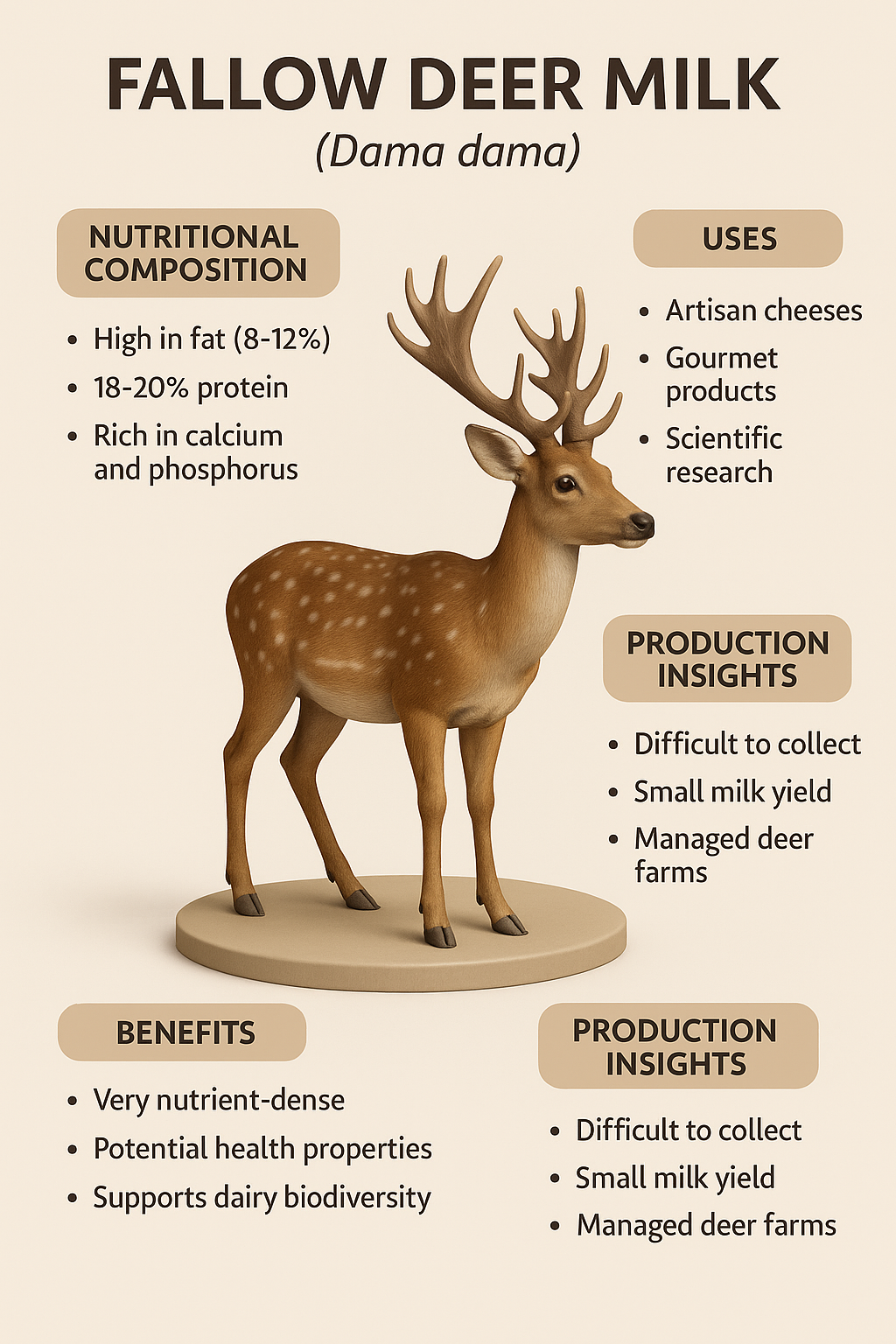

https://farmingwriters.com/fallow-deer-milk-complete-world-guide-ecology-nutrition/