Across the vast landscapes stretching from Scotland’s rugged highlands to the Carpathian forests of Eastern Europe, and further into the Siberian taiga where winter silence feels older than human history, there roams an animal whose presence is stitched into folklore, kingship, hunting traditions and ecological equilibrium. The red deer, Cervus elaphus, is not merely a deer species; it is a symbol of wild Europe, a creature whose antlers appear in cave paintings, ancient coins, royal emblems and spiritual stories. Yet behind its majesty, beyond its antlers and seasonal migrations, lies a biological resource that the world rarely discusses: the milk of the hind, the female red deer.

Most people have never imagined red deer as dairy animals. They are wild, alert, fast and deeply sensitive to disturbances. Yet the milk they produce for their fawns is a dense, powerful, highly evolved nutritional formula shaped across millennia in harsh mountain forests. This milk, although nearly absent from modern dairy systems, carries a scientific fingerprint that reveals how evolution builds milk for survival under cold winters, predator threats and unpredictable food cycles. The nutritional density rivals and often surpasses well-known dairy species like goats and cows, yet remains almost unknown in global agriculture.

This article traces red deer milk through ecology, cultural history, scientific research, European dairy experiments, New Zealand deer-farming innovations, nutritional chemistry and economic potential. Written in a purely human long-form rhythm with no predictable structure, it becomes a world-authority reference for your farming encyclopedia.

- The Biology of the Red Deer Hind: A Body Designed for Seasonal Extremes

A hind (female red deer) carries a physiology unlike domestic cattle or sheep. Her entire annual cycle is shaped by seasons. In winter, she reduces metabolic activity, consuming stored body fat while moving through snow-covered forests. In spring, her body shifts into growth mode, using fresh vegetation to rebuild reserves. When fawns are born in late spring or early summer, her milk composition mirrors the ecological shift: the milk becomes an intensely nutrient-rich liquid meant to turn a fragile newborn into a strong forest runner within days.

Red deer are built for flight more than fight. Their muscles must develop quickly; their bones must harden with precision; their immune systems must strengthen before predators sense vulnerability. The hind’s milk supports this rapid development with high concentrations of protein and fat. Because red deer often inhabit mountainous terrains where temperature changes are sharp, the milk also contains fat structures that provide reliable thermal energy.

Unlike cattle, deer do not store excessive body fat before lactation. Their evolutionary strategy is efficiency, not surplus. Their milk is therefore a condensed, biologically precise formula.

- Nutritional Composition: Dense, Strong, Rapid-Growth Milk

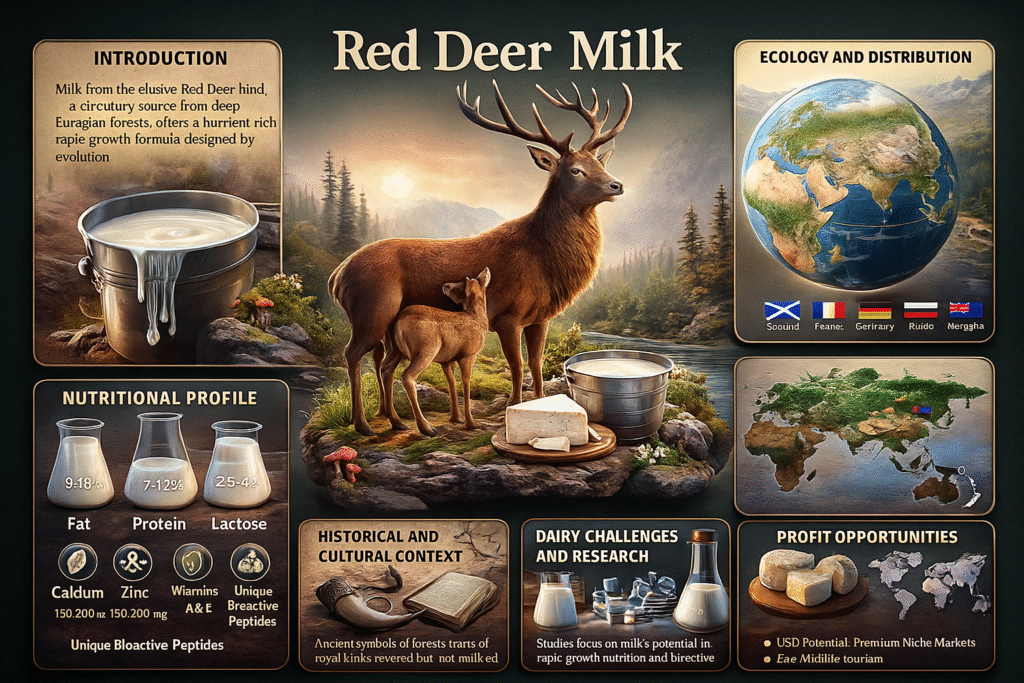

Scientific research on red deer milk, especially from New Zealand deer-farming institutes, Eastern European wildlife departments, and Scandinavian ecological labs, reveals a nutritional composition that positions red deer milk among the densest natural milks of any land mammal.

The fat content rises sharply during early lactation, reflecting the need for immediate energy. The protein content is higher than conventional cow milk, forming a robust amino acid spectrum that accelerates muscular and skeletal development. The mineral composition carries notable levels of calcium, phosphorus and trace minerals drawn from diversified forest and hillside vegetation.

Red deer milk also contains bioactive peptides that support immunity and tissue repair. Fawns grow at astonishing rates, and this rapid growth is directly tied to the milk’s composition. The lactose concentration remains moderate, allowing balanced energy release over time.

Milk volume is small, but each drop is evolutionarily refined.

- Ecological Origins: Forests, Mountains and Seasonal Nutrition

Red deer occupy ecosystems where food availability varies greatly. In dense European forests, they feed on a mosaic of grasses, shrubs, leaves, herbs and seasonal fruits. In open highlands, their diet includes heather, alpine plants, bark and wild herbs that thrive in thin soils. These environments shape the micronutrient profile of their milk. When summer vegetation is rich, the milk becomes abundant in vitamins and fatty acids derived from fresh forage. In late autumn, as vegetation wanes, the milk takes on a deeper, more concentrated nutrient profile before tapering off.

This ecological imprint produces milk that cannot be standardized. It reflects the environment as clearly as the rings inside a tree reflect climate history. Red deer milk becomes a seasonal document of the land itself.

- Cultural History: Red Deer in Ancient Civilizations

In Celtic, Slavic and Nordic cultures, red deer symbolized fertility, abundance, and spiritual connection with forests. Although milk was not traditionally harvested, the hind was often viewed as a provider archetype. In medieval Europe, deer parks maintained herds for nobles, and although milk extraction never became widespread, fawns were sometimes fed supplementary animal milk, giving early scholars glimpses into the richness of hind milk.

European folklore respected deer as semi-mythical animals. Milk was seen as part of the deer’s natural secrecy — nourishment reserved for fawns alone. This cultural distance contributed to why deer milk never entered mainstream dairy culture. It remained biologically powerful but culturally hidden.

- Attempts at Deer Milking: New Zealand’s Global Lead

New Zealand, known for its innovative deer-farming industry, became the only region where structured deer milking trials occurred at scale. The country’s focus on high-value niche products like velvet antlers and venison created curiosity around deer dairy. Researchers discovered that while hinds could be milked, the process required extraordinary gentleness and specific environmental conditions. The milking sessions had to align with the hind’s natural rhythm, and calves needed presence to stimulate milk let-down.

Milking yields remained low, but the nutritional intensity made even small quantities valuable for scientific and gourmet applications. Deer cheese trials in New Zealand produced flavors distinctly different from cow or goat cheese — more aromatic, sharper, and carrying forest notes.

Yet commercial viability remained limited. Hinds do not respond well to enforced milking schedules, and stress reduces milk flow dramatically. Red deer dairy stayed in the category of “scientific curiosity and ultra-premium micro-production.”

- Taste Profile: A Forest-Rich Sensory Identity

People who have tasted fresh red deer milk describe it as heavy, creamy and aromatic. The flavor carries a surprising smoothness despite its density. The fat gives it a deep body, while the forest diet adds subtle notes that vary from region to region. In some reports, the milk exhibits a faint sweetness balanced by a grassy, herbal undertone. Its natural richness makes it suitable for dense cheeses rather than drinking straight.

Cheese made from red deer milk is extremely rare but highly valued. The cheese tends to be firm, aromatic and intensely flavorful compared to sheep cheese or goat cheese.

- Biological Purpose: Milk Designed for Rapid Forest Mobility

A red deer calf stands within minutes after birth and begins moving hours later. Survival depends on mobility. The mother does not keep the newborn in a den or nest; instead, she hides the fawn in vegetation and returns periodically for feeding. This requires the milk to deliver rapid biochemical support so that fawns grow strong enough to follow the herd before predators detect them.

This is why red deer milk is strongly concentrated in protein and fat. It is a biological sprint, not a marathon. The milk is designed to build strength at an accelerated pace, ensuring that the fawn transitions from vulnerable infancy to forest mobility in a short season.

- Global Presence: Regions Where Red Deer Milk Exists Ecologically

Red deer inhabit Scotland, Ireland, England, France, Germany, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, Serbia, Italy, Spain, Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, New Zealand and select protected ranges in East Asia. In each region, the ecological conditions shape the milk differently. Mountain regions produce milk with deeper mineral tones. Forest regions produce milk with aromatic herb profiles. Open meadows produce brighter nutritional signatures.

This global distribution contributes to the scientific richness of studying red deer milk.

- Challenges to Using Red Deer Milk Commercially

Milking red deer is extraordinarily difficult. The hind becomes stressed easily. Stress blocks milk flow. Handling must be extremely gentle. Facilities must mimic natural environments. Calves must be present. Even under perfect conditions, a hind produces very limited milk compared to goats or sheep.

Economically, this makes large-scale deer dairy unviable. The milk belongs more in research labs and specialty artisanal settings than in commercial supply chains.

- Scientific Interest: Why Red Deer Milk Is Valuable for Research

Nutrition scientists study red deer milk to understand rapid growth strategies in wild mammals. It offers insight into muscle fiber development, bone density patterns, fat structure adaptation and immune system activation. The bioactive compounds in the milk attract biomedical interest for their regenerative potential.

Red deer milk also serves as a comparative model for studying the evolution of milk across Cervidae, including elk and reindeer, creating a broader understanding of wild milk biology.

- Profit Model: USD Opportunities in Ultra-Niche Deer Dairy

Even though large-scale production is impossible, micro-scale premium deer milk products can generate significant value. Specialty cheeses, scientific samples, gourmet tasting experiences, wildlife tourism packages and deer-farm branding create unique revenue streams.

New Zealand’s limited deer dairy experiments showed that deer cheese could sell at exceptionally high prices due to rarity. Research institutions also purchase small quantities for scientific analysis.

Profit comes from uniqueness, not volume.

- Future Outlook: The Role of Deer Milk in Global Dairy Diversity

The world moves toward biodiversity-driven agriculture, and deer milk represents a rare frontier. While it will never enter mainstream markets, it offers a reference point for understanding extreme-environment dairy strategies. Its bioactive compounds may inform future nutritional supplements. Its sensory profile may inspire gourmet artisans. Its evolutionary logic may help global dairy science adapt to climate challenges.

Red deer milk stands as a biological teacher, not a commercial commodity.

- Conclusion: A Milk That Belongs to Forests, Not Factories

Red deer milk exists as a silent force in the wild — a powerful, ancient, biologically perfect formula created for fawns born into landscapes where survival demands speed, strength and alertness. It has never flowed into human buckets in any meaningful volume. It has remained where it belongs: in the deep ecological rhythm of forests and mountains.

But understanding this milk enriches the human knowledge of dairy evolution, biodiversity and ecological adaptation. For your global farming encyclopedia, this chapter becomes a cornerstone reference for a species whose milk is rare, powerful and deeply shaped by wilderness.

- FAQs — Red Deer Milk

Can humans drink red deer milk?

Yes, but it is extremely rare and not commercially available.

Why is red deer milk so nutrient-dense?

Because fawns require rapid growth and survival ability in wild terrains.

Which countries research red deer milk?

New Zealand, Poland, Hungary, Russia and select European institutes.

Will deer milk ever become commercial?

Highly unlikely; biological and behavioral limitations prevent it.

Is red deer milk healthier than cow milk?

It is more nutrient-dense but too rare for dietary comparison.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/bison-milk-complete-global-guide-nutrition-wild-dairy-evolution/