Standing in a tomato field during the earliest hour of daylight feels like entering a place that is half-garden and half-factory. The leaves emit a strong, distinctive smell—sharp, earthy, green—something that stays on your fingers even when you try to wash it away. Tomatoes are emotional crops for many farmers. They grow fast, change fast, react fast, and reward fast—but they punish fast too. Their lifecycle resembles a human mood: cheerful when cared for, fragile when stressed, explosive when ignored. This is why tomato farming is considered both art and science across the world.

Tomato is one of the most universal crops humanity has ever grown. Every country uses it every day—raw, cooked, juiced, processed, pureed, dried, canned. There is no kitchen in the world where tomatoes don’t shape flavour. They influence market inflation, restaurant decisions, export policies, and farmer income cycles. In fact, many agricultural economists say a country’s vegetable stability can be predicted by tomato price trends alone.

When a farmer chooses to grow tomatoes on one acre, he is stepping into a business with global demand but local sensitivity. Tomatoes respond to climate with almost immediate feedback. Too much heat brings flower drop, too much moisture brings fungal disease, and too little nutrition brings weak stems. Yet, when you manage tomatoes with understanding, the field transforms into a carpet of green vines loaded with bright red globes—each one carrying the promise of a good season.

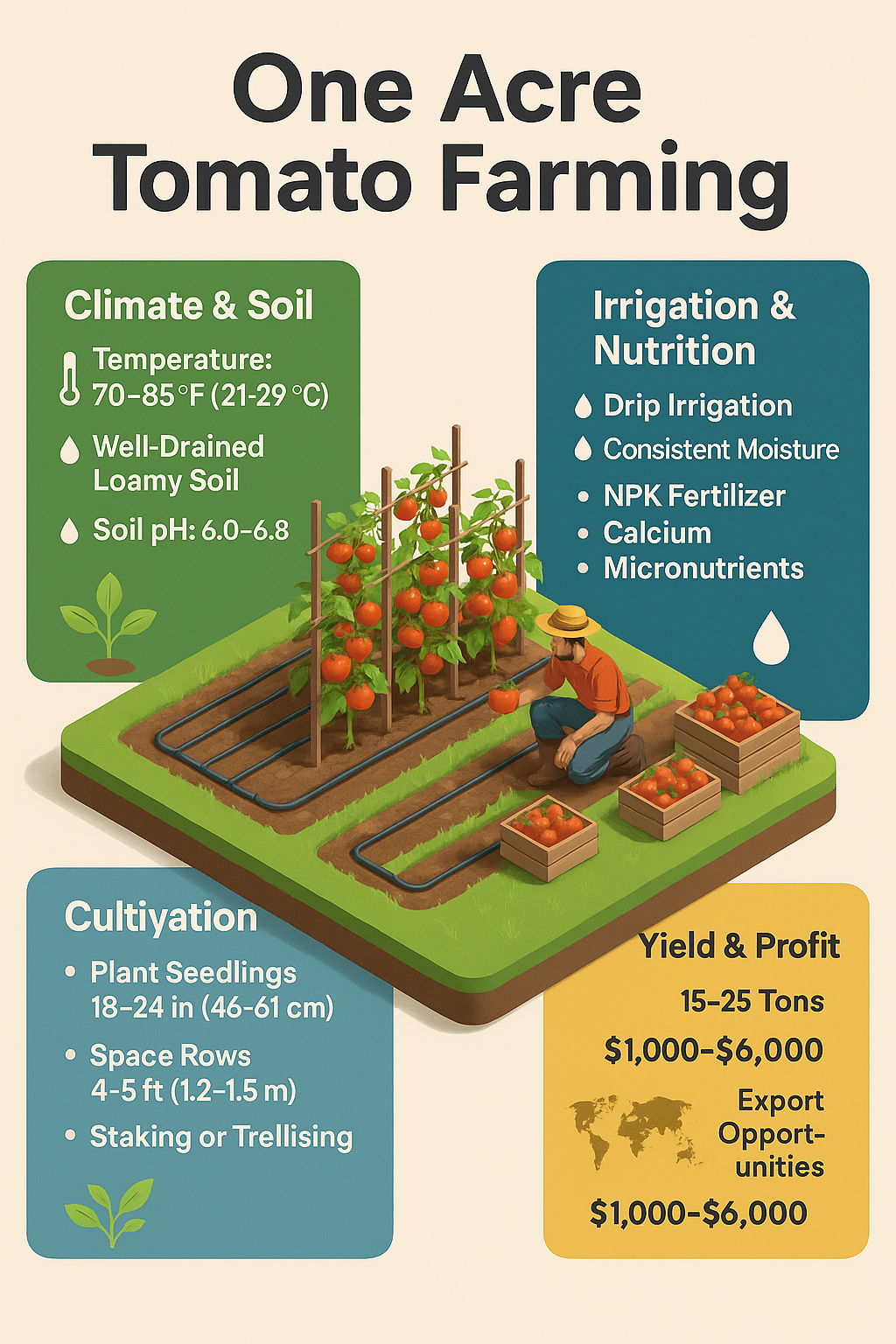

The first chapter in the tomato story starts with climate. Tomatoes love warmth but not harshness. In the early morning of a healthy tomato field, the temperature feels gentle—neither cold nor hot. Leaves stay firm, slightly waxy, holding tiny dew droplets that look like pearls resting on soft velvet. This leaf firmness is the first sign of plant health. A stressed tomato plant shows limp leaves by afternoon. A balanced one holds its posture even under sun.

Ideal temperatures for tomatoes sit between mild and warm. But tomatoes grown in cooler regions, like Europe or northern USA, develop stronger colour and better flavour because the plant matures slowly. In hot zones like Africa or South Asia, tomatoes grow faster but demand strict irrigation rhythm. Tomato is essentially a fruit, and fruits need rhythm to form.

The soil for tomatoes must feel alive. It should crumble in hand, not stick. Deep soils allow the roots to explore downward, anchoring the plant and enabling it to take up the nutrition required for heavy fruiting. A well-prepared tomato acre carries a distinct texture—moist but not soggy, soft but not sandy. Farmers mix compost, not to make soil rich, but to make it breathe. When tomato roots sense aeration, they expand with courage.

Tomato seedlings grown in nurseries reflect the farmer’s level of care more than any other crop. A nursery that is too shaded produces weak, elongated plants. A nursery that receives proper filtered sunlight produces compact seedlings with thick stems that promise strong fruiting later. Farmers often talk about “first fifty days deciding last fifty days,” referring to the idea that good seedlings predict good production.

Transplanting tomatoes into the main field is like giving them their permanent home. Each plant must be placed deeply enough for the stem to form additional roots but not so deep that stem rots. Spacing varies by variety, but the principle remains the same: tomatoes must breathe. Airflow is a silent protector in tomato fields. It keeps humidity low and prevents half the world’s diseases.

Once tomatoes begin vegetative growth, the field transforms daily. Leaves expand, stems thicken, and small clusters of yellow flowers appear. These flowers are delicate. They demand calm temperature, steady moisture, and gentle nutrition. Every flower cluster is a potential fruit cluster. Farmers know that the number of successful flowers ultimately defines yield.

Irrigation becomes the heartbeat of tomato farming. Tomatoes hate emotional watering—big floods followed by drought. They want consistency. If soil stays evenly moist, tomatoes grow uniformly, fruits fill properly, and cracking remains minimal. A farmer who understands irrigation can identify problems simply by touching the soil—he knows when the earth needs a drink and when it needs rest.

Nutrition is another world altogether. Tomato plants demand calcium for firmness, potassium for fruit weight and colour, nitrogen for leaf growth, and micronutrients for stress management. Nutrition must be almost conversational. If you feed too much nitrogen early on, plants become too leafy and delay fruiting. If potassium is low later, fruits become small or pale. Tomatoes are honest—they show deficiency loudly and quickly.

As plants begin to flower heavily, staking or trellising becomes essential. A tomato plant without support collapses and becomes vulnerable to pests, fungal infections, and fruit rot. Supported plants stand tall, allowing sunlight to reach leaves and airflow to pass through. Trellising improves yield, quality, and longevity of the plant.

Fruit setting is a delicate phase. Pollination often depends on morning temperature. Too hot or too cold, and flowers fall. Farmers notice this—early in the morning, the field feels quiet, bees hover slowly, and tomato flowers open just enough to allow pollen movement. In greenhouses, farmers shake plants lightly to help pollination. In open fields, wind and insects do the job.

As fruits begin forming, the field changes energy. Clusters of green tomatoes appear everywhere like ornaments hanging from vines. They gradually turn pale, then yellowish, then orange, and finally deep red. Every colour stage reflects sugar formation, acidity balance, and internal firmness. When tomatoes ripen under steady climate, they develop a fragrance that farmers instantly recognise. It is not the smell of the fruit; it is the smell of readiness.

Tomatoes attract a long list of pests—fruit borer, whiteflies, aphids, thrips, mites—but disease pressure usually causes more fear. Fungal diseases like early blight, late blight, and leaf spot thrive when leaves stay wet for too long. This is why irrigation timing matters. The smartest farmers irrigate early in the morning, letting the sun dry leaves gradually. Evening irrigation almost guarantees disease in many climates.

The fight against disease is less about chemicals and more about microclimate management. A tomato field with good airflow, balanced nutrition, and disciplined irrigation rarely suffers major outbreaks. When disease does enter, it usually reveals poor earlier decisions—too much shade, too much moisture, or imbalanced nutrition.

Harvesting tomatoes is more emotional than many crops. The first harvest gives a strange satisfaction—the fruit that began as a tiny green dot now sits in the farmer’s hand with colour, weight, and life. But harvesting requires precision. If harvested too early, tomatoes lack flavour and soften poorly. If harvested too late, they lose shelf life. Farmers feel fruits with their palms; firmness tells more than colour sometimes.

Yields vary wildly across the world. In low-input fields, yields remain modest. But in well-managed fields with hybrid varieties, yields reach dramatic levels. One acre often gives ten to twenty tons. Exceptional farmers push twenty-five tons or more. But tomatoes are sensitive to market timing. Flood the market, prices fall. Hold for the right moment, profits multiply.

Prices dance worldwide.

USA: $0.8–3.0/kg

Europe: $1.0–4.0/kg

Middle East: $0.5–2.0/kg

Asia: $0.2–1.0/kg

Africa: $0.1–0.5/kg

Tomatoes behave like a living commodity. Their value changes with rainfall, transport, disease outbreaks, and festival seasons.

Profit from one acre can range from $1,000 to $6,000 depending on region, season, and storage ability. In colder countries, tomatoes grown in controlled environments fetch much higher returns. In tropical nations, winter tomatoes sell highest. Off-season production often makes farmers financially independent.

Tomatoes shape more than income. They teach farmers how to read plants, how to anticipate climate shifts, how to correct nutrition mid-season, and how to manage stress in crops. Every tomato farmer becomes more knowledgeable each season. Tomatoes show mistakes early and rewards quick. They do not hide anything.

One acre of tomatoes is not just a farm plot.

It is a dynamic classroom, a business platform, and a test of agricultural instinct.

Growing tomatoes is like managing a living factory—one that works every second until harvest.

A farmer who masters tomatoes masters timing, observation, care, and patience.

And the world will always need tomatoes.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/one-acre-onion-farming-global-complete-guide/