Turmeric fields do not announce themselves loudly. There are no flashy colours at the beginning, no dramatic flowering stage, no immediate return. Instead, turmeric farming feels calm, steady, and deeply rooted—both literally and economically. When you stand in a turmeric field after the first monsoon rain or early irrigation, the air carries a warm, earthy fragrance mixed with something faintly medicinal. It is subtle but recognisable. Farmers with experience can identify turmeric fields blindfolded just by smell.

Turmeric is not a fast crop. It is a trust crop. Farmers who choose turmeric on one acre are choosing patience, long-term planning, and global relevance. Turmeric does not depend on one cuisine, one culture, or one market. It is used in kitchens, medicine cabinets, cosmetic factories, religious rituals, pharmaceutical labs, and even textile industries. Very few crops enjoy such universal respect.

Across the world, turmeric adapts quietly.

In India, it grows as a traditional cash crop tied to monsoon rhythm.

In Southeast Asia, it thrives in humid climates, growing vigorously under partial shade.

In Africa, turmeric has emerged as a high-potential export spice, prized for colour strength.

In Europe and North America, turmeric is increasingly grown for organic and medicinal markets, where quality matters more than volume.

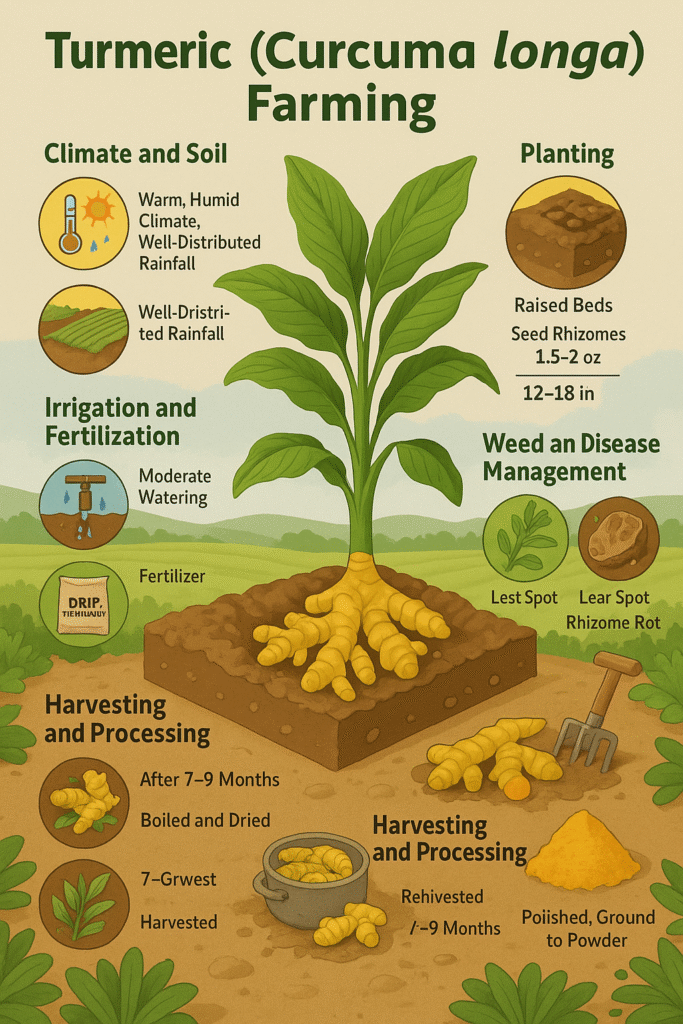

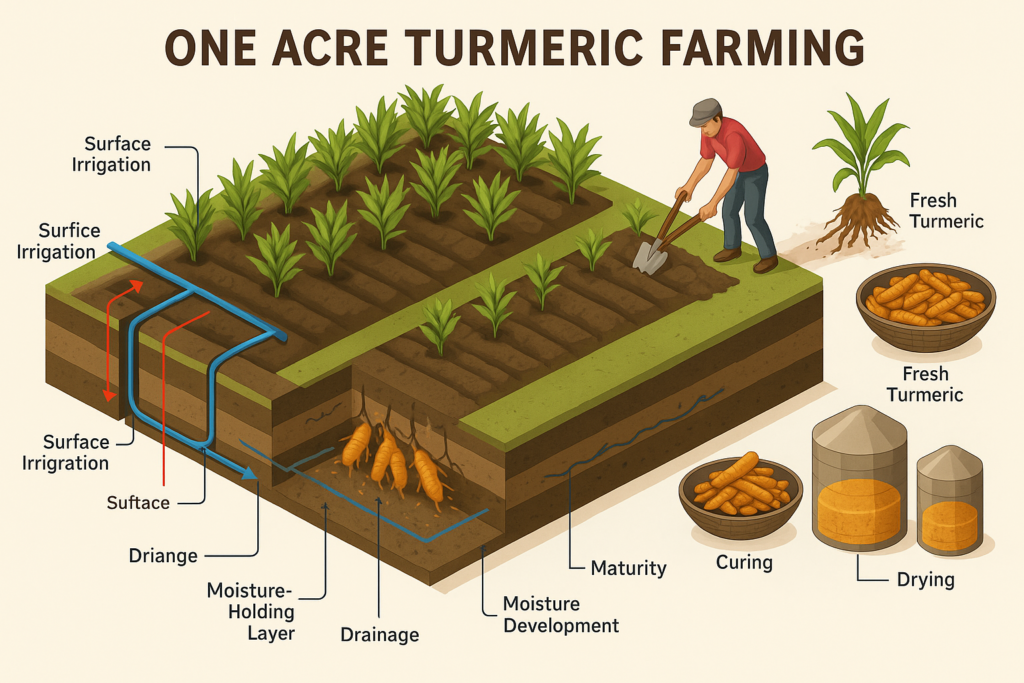

One acre of turmeric farming begins with soil that feels forgiving. Turmeric rhizomes expand horizontally, pushing gently through the soil as they grow thicker and longer. Hard soils restrict this movement, producing small, malformed fingers. Ideal turmeric soil feels loose, deep, and warm. When you dig your fingers into good turmeric soil, it should not resist. It should open easily, holding moisture without becoming sticky.

Climate decides turmeric personality. The crop loves warmth, moderate humidity, and steady moisture. Turmeric dislikes sudden cold, prolonged drought, and waterlogging. It thrives in temperatures where the air feels comfortably warm rather than hot. This is why turmeric aligns naturally with monsoon-fed systems and controlled irrigation systems equally well.

Planting turmeric is unlike seed-based crops. What you put into the ground is not a seed but a living rhizome filled with stored energy. Each rhizome is already a plant waiting to wake up. Farmers select healthy, disease-free turmeric fingers carefully. Large, plump rhizomes produce stronger plants. Weak or shrivelled rhizomes result in uneven growth that never truly recovers.

When turmeric is planted, the field looks empty for weeks. This is where inexperienced farmers panic. But underground, something intense is happening. The rhizomes swell, emit roots, and send shoots upward quietly. When the first green leaves finally break the soil surface, they unfold slowly, wide and glossy, almost like banana leaves in miniature. This stage confirms that the invisible work beneath the earth is underway.

Turmeric irrigation must follow patience rather than force. Too much water rots rhizomes silently beneath the soil. Too little water stalls growth permanently. Farmers who succeed with turmeric learn to read soil moisture by touch rather than schedule. They water when soil begins to lose coolness, not when it becomes dry. Consistency builds uniform rhizomes, which matter greatly in global spice markets.

Nutrition in turmeric serves two goals: vegetative strength above ground and rhizome expansion below ground. Nitrogen supports leaf development, but excess nitrogen delays rhizome maturity. Potassium strengthens finger formation, colour intensity, and storage life. Organic matter plays a larger role here than in many vegetables, providing slow nutrition and improving soil behaviour over the long growing season.

Weed pressure is heavy in turmeric fields during early growth. Because turmeric grows slowly at the beginning, fast-growing weeds easily dominate if ignored. Farmers invest effort in early field cleanliness, knowing that once leaves spread and shade the ground, weed pressure reduces naturally. Clean early growth leads to stress-free later months.

Turmeric pests rarely attack aggressively above ground, but underground pests can cause silent damage. Rhizome rot, nematodes, and fungal infections typically arise from poor drainage or contaminated planting material. Farmers who rotate crops and avoid turmeric after turmeric protect their soil naturally. Disease prevention in turmeric is more about discipline than treatment.

As months pass, turmeric plants grow tall, forming a lush canopy that hides the soil completely. The field feels alive and humid even on warm days. At this stage, the farmer’s role reduces. The crop largely manages itself if early decisions were correct. Leaves capture sunlight, transport energy downward, and enlarge rhizomes steadily.

Maturity announces itself through decline. Leaves slowly turn yellow, then dry. This is not sickness; it is completion. When most foliage naturally collapses, the underground rhizomes have reached full size and potency. Farmers resist the temptation to harvest early, because turmeric gains colour and weight significantly in its final weeks.

Harvesting turmeric feels heavy. Rhizomes emerge coated in soil, thick, knotted, and aromatic. Hands get stained yellow instantly. The smell fills the air. At this moment, turmeric reveals its real value. Fresh weight feels impressive, but every farmer knows that processing decides final profit.

After harvest, turmeric undergoes curing and drying. Boiling, drying, polishing—each step affects colour, aroma, and market grade. This is where turmeric shifts from crop to commodity. Poor processing destroys value. Good processing multiplies it.

Yield per acre varies with variety and care.

Traditional yields range between 6–8 tons fresh rhizome.

Improved practices reach 10–12 tons.

High-performing fields exceed this.

Dry turmeric yield usually stands around one-fifth of fresh weight.

Global turmeric prices depend heavily on quality.

USA: $3–10/kg (organic grade higher)

Europe: $4–12/kg

Middle East: $3–8/kg

Asia: $1–4/kg

Africa: $2–6/kg

Export-grade turmeric earns far more than bulk market turmeric. Colour strength, aroma, cleanliness, and moisture content make the difference.

Profit from one acre of turmeric ranges widely.

Low-input systems earn modest but stable returns.

Well-managed export systems earn $4,000–$8,000 per acre.

Organic and value-added turmeric exceeds this significantly.

Turmeric does not rush farmers, and farmers should not rush turmeric. It teaches long-term thinking, soil respect, and process discipline. It is a crop that grows quietly but sells loudly across the world.

One acre of turmeric is not about speed.

It is about depth, consistency, and trust in the invisible.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love Farming Love Farmers

Read A Next Post 👇

https://farmingwriters.com/one-acre-cucumber-farming-complete-global-guide/