Most farmers don’t fail in onion farming because they can’t grow onions.

They fail because onions grow too easily.

This is the first contradiction that destroys profits.

Every year, lakhs of farmers across India, Africa, and parts of Asia harvest good onion crops. Bulbs look healthy. Fields look dense. Yield numbers look impressive. And yet, the moment onions reach the market, prices collapse so sharply that harvesting itself becomes a loss-making activity. Many farmers abandon harvested onions in fields, not because production failed, but because marketing did.

The biggest problem with onion farming is not agronomy.

It is timing, volume pressure, and buyer psychology.

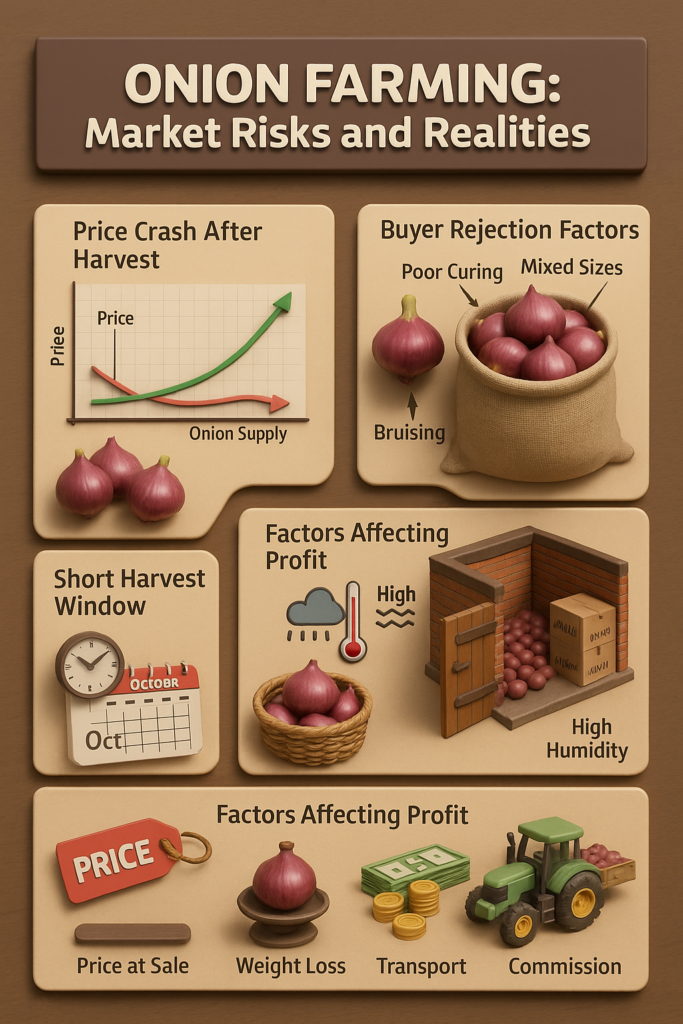

Most online advice talks about seed rate, fertilizer dose, irrigation schedule. That knowledge is everywhere. What is rarely discussed is this: onions are rejected or devalued even when they look “good” to the farmer. Buyers grade onions using parameters farmers are seldom told about, such as neck thickness, skin tightness, shine, uniformity, curing quality, and storage potential.

The moment onion supply floods the market, buyers stop negotiating. They dictate prices. Farmers usually realize too late that onion is not a “sell anytime” crop. It is a sell-only-at-the-right-window crop.

Many new farmers enter onion farming after seeing high prices in one season. They assume the crop itself is profitable. That assumption alone is enough to cause loss.

WHERE ONION FARMING BREAKS DOWN IN REAL LIFE

One of the most damaging myths is that onion is a “safe crop” because demand is always present. Demand may be constant, but price acceptance is not.

During peak harvest periods, markets receive onions with varying moisture levels, skin maturity, and storage capacity. Buyers immediately separate onions into categories: export quality, storage grade, immediate consumption grade, and reject stock. Farmers usually fall into the last two categories without realizing it.

A common failure point is improper curing. Onions harvested with green necks or insufficient skin layers do not store well. Buyers penalize such stock heavily because they lose weight rapidly and rot sooner. Even if yield is high, poor curing converts potential profit into instant loss.

Another ignored factor is uniformity. Mixed-size onions reduce buyer interest. Large trading buyers prefer uniform lots for storage and resale. Small and medium bulbs are pushed into local markets where price volatility is extreme.

Transportation damage quietly eats profit. Bruised onions may look fine initially but soften during storage, leading buyers to reject entire loads. Farmers rarely factor transport losses into cost calculations.

PRODUCTION IS EASY — DECISION IS HARD

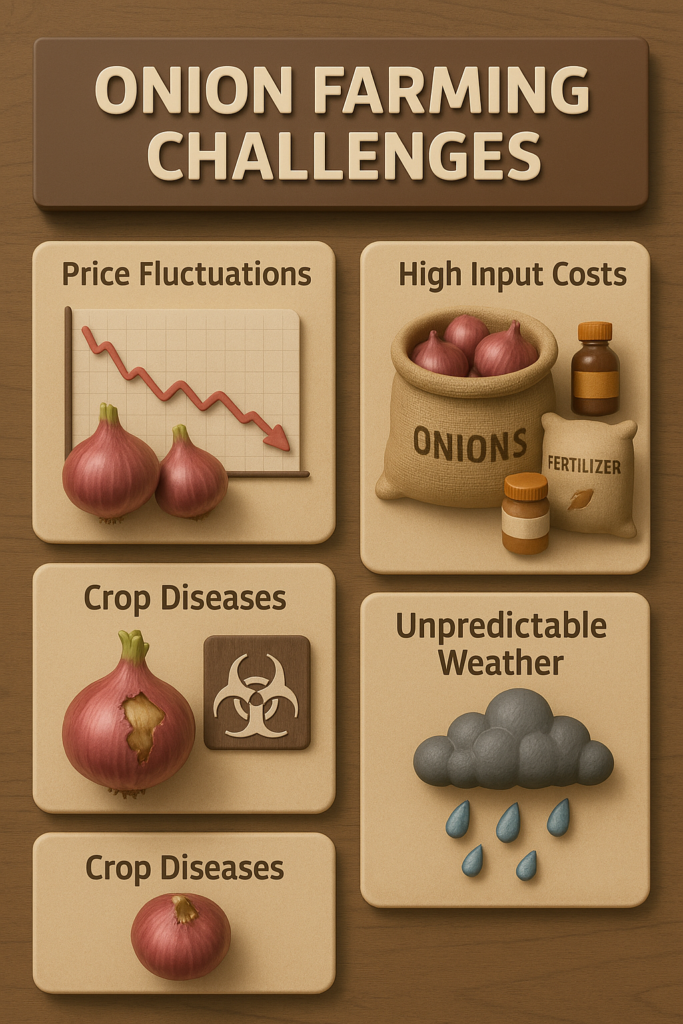

Onion grows under a wide range of climates. This adaptability is precisely why oversupply repeats every year. When weather favors production across regions, markets collapse simultaneously.

Farmers often expand onion area without checking regional planting trends. A single WhatsApp advisory or neighbor advice leads to mass sowing. By the time farmers realize congestion, the crop is already in the ground.

Unlike fruits, onions cannot be staggered easily once planted. Everyone harvests within the same window. Storage requires infrastructure, which most small holders lack. As a result, forced selling begins.

Another overlooked risk is policy shock. Export bans, minimum export prices, and sudden import decisions directly crush onion prices overnight. Farmers have zero control over this risk, yet most ignore it while planning.

WHEN ONION FARMING MAKES SENSE AND WHEN IT DOES NOT

Onion farming only works sustainably when at least one of the following is true:

You can store onions safely for several months

or

You target a specific off-season market window

or

You grow a variety demanded by exporters or processors

If none of these conditions apply, onion farming becomes a gamble.

Farmers working with good drying weather, low humidity, and access to ventilated storage stand a chance to wait for price recovery. Farmers harvesting during humid or rainy periods are exposed to rapid spoilage. In such zones, onion farming is structurally high risk.

Short-day varieties grown purely for bulk fresh market sales suffer the highest price crashes. Long-day varieties with better keeping quality offer more flexibility but take longer to mature and carry higher input costs.

BUYER BEHAVIOR THAT SURPRISES FARMERS

Buyers do not pay for yield; they pay for risk reduction.

An onion that stores well, loses less weight, and stays firm is valuable.

A wet-looking onion with soft neck is a liability.

Farmers often assume buyers try to cheat. In reality, buyers price risk aggressively. When supply is abundant, they avoid marginal quality altogether.

Another hard truth: local mandis are the worst place to discover onion’s real value. Prices fluctuate wildly based on arrivals. Professional buyers often source directly from farms that meet strict quality requirements, bypassing open markets entirely. Farmers without access to such buyers are exposed to daily price swings.

COST VS PROFIT — THE ILLUSION

Many farmers calculate profit based on cost of cultivation versus peak market price they saw on news channels. That calculation is meaningless.

Real profit depends on price at the day of actual sale, not the month’s high. Transport cost, commission, spoilage loss, weight loss during storage, and interest on borrowed capital quietly eat margins.

A farmer who produces 25–30 tons per hectare can still lose money if selling during market glut. Meanwhile, a farmer with 15 tons but correct timing and grade can earn more.

Yield is not the hero in onion farming.

Timing is.

FAQ — ONION FARMING (REAL QUESTIONS)

Farmers often ask why onion prices crash suddenly, and the answer lies in synchronized harvesting across regions combined with buyer risk aversion.

Another common doubt is whether storage guarantees profit, and the reality is storage only helps if curing quality and ventilation are correct.

Many growers ask if export saves farmers, but export favors only specific grades and varieties.

Questions arise about why visually good onions get rejected, and the reason is internal moisture and neck condition.

Farmers ask whether small bulbs are useless, and they usually fetch lower prices unless tied to processing buyers.

Another doubt is about fertilizer increase to boost size, but excess nitrogen worsens storage quality.

Many ask if onion always recovers price later, and the truth is some seasons never recover.

Growers ask whether late harvesting helps, but delayed harvest in humid weather increases rot risk.

Some ask if mechanized farming improves profit, and it helps only when scale and storage match.

Finally, farmers ask who should avoid onion farming, and the answer is anyone without storage, timing control, or risk tolerance.

FINAL TAKEAWAY

Onion farming is not a production challenge.

It is a decision and market-timing challenge.

Farmers who plant onions just because prices were high last year are preparing for loss. Those who understand buyer behavior, storage realities, and policy risk give themselves a real chance.

Onion does not forgive wrong timing.

✍️Farming Writers Team

Love farming Love Farmers